There is little evidence on the optimal strategy for bifurcation lesions in the context of a coronary chronic total occlusion (CTO). This study compared the procedural and mid-term outcomes of patients with bifurcation lesions in CTO treated with provisional stenting vs 2-stent techniques in a multicenter registry.

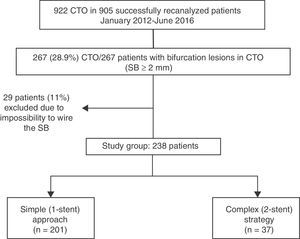

MethodsBetween January 2012 and June 2016, 922 CTO were recanalized at the 4 participating centers. Of these, 238 (25.8%) with a bifurcation lesion (side branch ≥ 2mm located proximally, distally, or within the occluded segment) were treated by a simple approach (n=201) or complex strategy (n=37). Propensity score matching was performed to account for selection bias between the 2 groups. Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) consisted of a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction, and clinically-driven target lesion revascularization.

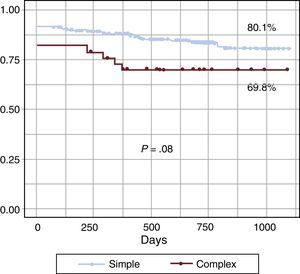

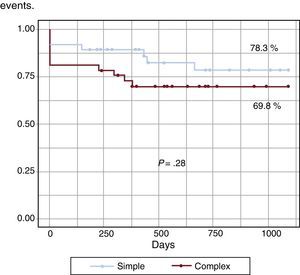

ResultsAngiographic and procedural success were similar in the simple and complex groups (94.5% vs 97.3%; P=.48 and 85.6% vs 81.1%; P=.49). However, contrast volume, radiation dose, and fluoroscopy time were lower with the simple approach. At follow-up (25 months), the MACE rate was 8% in the simple and 10.8% in the complex group (P=.58). There was a trend toward a lower MACE-free survival in the complex group (80.1% vs 69.8%; P=.08). After propensity analysis, there were no differences between the groups regarding immediate and follow-up results.

ConclusionsBifurcation lesions in CTO can be approached similarly to regular bifurcation lesions, for which provisional stenting is considered the technique of choice. After propensity score matching, there were no differences in procedural or mid-term clinical outcomes between the simple and complex strategies.

Keywords

Randomized trials of bifurcation lesions have not demonstrated the advantages of systematic side branch (SB) stenting compared with a 1-stent strategy.1–8 Consequently, provisional SB stenting is the current preferred strategy for the percutaneous treatment of this type of lesion.

Bifurcation lesions in the context of a coronary chronic total occlusion (CTO) represent an additional challenge that has received little scrutiny. It is unclear whether the recommendations for the treatment of bifurcation lesions in the context of nonocclusive coronary artery disease are applicable in this scenario. Specific factors, such as the dissection frequently observed during CTO recanalization or the complexity of the procedure (ie, operator fatigue) could influence the strategy chosen and subsequently patient outcomes.

The aim of this study was to compare the procedural and mid-term clinical outcomes of patients with bifurcation lesions in CTO treated with provisional T-stenting (simple strategy) vs 2-stent techniques (complex strategy) in a multicenter registry.

METHODSPatient PopulationWe included all consecutive patients who underwent CTO percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with successful wire crossing of the occlusion, and a SB ≥ 2mm taking off at the proximal or distal cap, or within the occluded segment. Proximal and distal SB were included when the distance between the SB and the occluded segment was ≤ 5mm. The procedures were performed by experienced CTO-PCI operators at the 4 participating centers between January 2012 and June 2016. A total of 922 CTO in 905 patients were recanalized. Of these, 267 CTO in 267 patients involved a bifurcation lesion (29.0%). Twenty-nine (11%) patients were excluded due to the impossibility of wiring the SB before or after main vessel stent implantation despite the operator's intention. The remaining 238 patients (26.2%) were treated by the simple approach (n=201) or complex strategy (n=37). The study flowchart is shown in Figure 1. Written informed consent for treatment and data analysis was obtained from all patients.

ProcedureThe decision to use an antegrade or retrograde approach and the CTO crossing strategy was at the operator's discretion after a thorough study of the CTO anatomy using simultaneous double injection when applicable. Bifurcation lesions were divided into 3 types regarding the SB take-off from the main vessel: bifurcation lesions within the occluded segment, those located at the distal cap, and those at the proximal cap. The type of bifurcation treatment was also at the discretion of the operator.

The patients were pretreated with dual antiplatelet medication. In the cardiac catheterization laboratory, weight-adjusted heparin was administered to maintain an activated clotting time for > 300seconds and was monitored every 30minutes to determine whether an additional bolus of unfractionated heparin was necessary. After the procedure, all patients received 100mg of aspirin daily indefinitely and a maintenance dose of clopidogrel (75mg/d), prasugrel (10mg/d) or ticagrelor (90mg twice daily) for 6 to 12 months. In all patients, serial determinations of troponin levels were performed before and every 6hours after the procedure for the first 24hours.

Angiographic DataQuantitative coronary analysis was performed before and after the procedure using the dedicated bifurcation software CAAS 5.11 (Pie Medical Imaging BV, Maastricht, The Netherlands). The following parameters were measured on the main vessel: reference vessel diameter, occlusion segment length, lesion segment length, final minimal lumen diameter, and final percentage of stenosis. In the SB, the parameters obtained were the reference diameter, minimal lumen diameter and percentage of baseline stenosis, final minimal lumen diameter, and final percentage of stenosis.

DefinitionsCoronary chronic total occlusion was defined as a 100% stenosis with thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade 0 with an estimated duration of more than 3 months.9 The J-CTO score10 was calculated for each lesion. The baseline bifurcation anatomy was assessed according to the Medina classification.11 In SB located within the occluded segment or distally, the presence of ostium disease was studied by analyzing the filling of the SB by collaterals. True bifurcations were considered: (1,1,1), (0,1,1), and (1,0,1) of the Medina classification. Technical success of CTO recanalization was defined as a residual stenosis < 30% with TIMI flow grade 3 in the main vessel.12 Bifurcation technical success was considered to occur when a residual stenosis of < 30% in the main vessel and a final TIMI flow grade 3 in both branches were obtained.13 Procedural success was defined as angiographic success plus the absence of in-hospital adverse events (all-cause death, myocardial infarction [MI], stroke, recurrent angina requiring target-vessel revascularization with PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting, and tamponade requiring pericardiocentesis or surgery).12

Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) on follow-up were defined as a composite of cardiac death, MI, and clinically-driven target lesion revascularization. All deaths without a clear noncardiac cause were considered to be cardiac deaths. Periprocedural MI was defined as elevation of cardiac troponin values (> 5 × 99th percentile upper-reference limit) in patients with normal baseline values (≤ 99th percentile upper-reference limit) or as a rise in cardiac troponin values > 20% if baseline values were elevated and had been either stable or falling.14 Definite or probable stent thrombosis was adjudicated according to the Academic Research Consortium criteria.15

Follow-upClinical follow-up was performed by means of a review of hospital records, outpatient visit, or phone calls. Patients with symptom recurrence or with inducible ischemia were recommended to undergo angiographic evaluation.

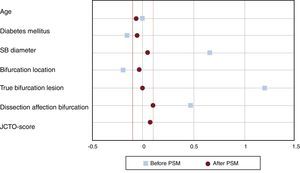

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, if normally distributed, or the median [interquartile range: IQ25-75] if the distribution was nonnormal and were compared using the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages and were compared using the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Major adverse cardiac events free survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were evaluated with the log-rank test. To account for selection bias between the simple and complex group, propensity score adjustment was performed using a genetic search algorithm and 1:1 matching. The propensity score was estimated with multivariable logistic regression for complex treatment probability including clinical, angiographic, and procedural variables potentially associated with complex PCI and the primary endpoint. The following covariates were included in the propensity score calculation: age, diabetes, SB diameter, true bifurcation lesions, dissection affecting bifurcation point, bifurcation location, and J-CTO score. Standardized differences were calculated for all covariates before and after matching to assess balance after matching (Figure 2). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19 and R version 3.4.0 for Windows. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

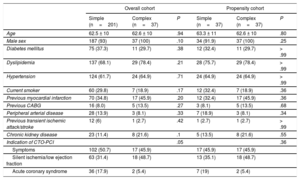

RESULTSBaseline Clinical CharacteristicsThe clinical characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1. No differences were observed with regard to cardiovascular risk factors, chronic kidney disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, and prior MI, PCI, or coronary artery bypass grafting. However, the indication of CTO-PCI for acute coronary syndrome was more frequent in the simple approach group.

Clinical Characteristics

| Overall cohort | Propensity cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple (n=201) | Complex (n=37) | P | Simple (n=37) | Complex (n=37) | P | |

| Age | 62.5 ± 10 | 62.6 ± 10 | .94 | 63.3 ± 11 | 62.6 ± 10 | .80 |

| Male sex | 187 (93) | 37 (100) | .10 | 34 (91.9) | 37 (100) | .25 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 75 (37.3) | 11 (29.7) | .38 | 12 (32.4) | 11 (29.7) | > .99 |

| Dyslipidemia | 137 (68.1) | 29 (78.4) | .21 | 28 (75.7) | 29 (78.4) | > .99 |

| Hypertension | 124 (61.7) | 24 (64.9) | .71 | 24 (64.9) | 24 (64.9) | > .99 |

| Current smoker | 60 (29.8) | 7 (18.9) | .17 | 12 (32.4) | 7 (18.9) | .36 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 70 (34.8) | 17 (45.9) | .20 | 12 (32.4) | 17 (45.9) | .36 |

| Previous CABG | 16 (8.0) | 5 (13.5) | .27 | 3 (8.1) | 5 (13.5) | .68 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 28 (13.9) | 3 (8.1) | .33 | 7 (18.9) | 3 (8.1) | .34 |

| Previous transient ischemic attack/stroke | 12 (6) | 1 (2.7) | .42 | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) | > .99 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 23 (11.4) | 8 (21.6) | .1 | 5 (13.5) | 8 (21.6) | .55 |

| Indication of CTO-PCI | .05 | .36 | ||||

| Symptoms | 102 (50.7) | 17 (45.9) | 17 (45.9) | 17 (45.9) | ||

| Silent ischemia/low ejection fraction | 63 (31.4) | 18 (48.7) | 13 (35.1) | 18 (48.7) | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 36 (17.9) | 2 (5.4) | 7 (19) | 2 (5.4) | ||

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CTO, coronary chronic total occlusion; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or No. (%).

There were no differences between groups in terms of the target vessel CTO, J-CTO score, or location of the bifurcation lesion (Table 2). However, in the complex group, the SB was larger (2.53 ± 0.38 vs 2.30 ± 0.29mm; P < .01) and a true bifurcation was also encountered more frequently (92% vs 43%; P < .01) (Table 2). Additionally, after PCI, quantitative coronary data showed a larger minimal lumen diameter and lower percentage of stenosis at the SB in the complex group.

Angiographic Data

| Overall cohort | Propensity cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple (n=201) | Complex (n=37) | P | Simple (n=37) | Complex (n=37) | P | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 50.9 ± 11 | 48.7 ± 12 | .26 | 48.9 ± 14 | 48.7 ± 12 | .87 |

| Number of diseased vessels | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | .70 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.7±0.8 | .74 |

| Target-vessel CTO | .58 | .36 | ||||

| LAD | 85 (42.3) | 18 (48.7) | 16 (43.2) | 18 (48.7) | ||

| LCx | 56 (27.9) | 11 (29.7) | 12 (32.4) | 11 (29.7) | ||

| RCA | 60 (29.8) | 8 (21.6) | 9 (24.3) | 8 (21.6) | ||

| J-CTO score | 1.87±1.1 | 1.95±1.2 | .70 | 1.86±1.1 | 1.95±1.2 | .76 |

| In stent CTO | 21 (10.4) | 5 (13.5) | .58 | 5 (13.5) | 5 (13.5) | > .99 |

| Medina classification | < .01 | > .99 | ||||

| True bifurcation | 88 (43.8) | 34 (91.9) | 34 (91.9) | 34 (91.9) | ||

| Nontrue bifurcation | 113 (56.2) | 3 (8.1) | 3 (8.1) | 3 (8.1) | ||

| Bifurcation location | .58 | > .99 | ||||

| Proximal cap | 79 (39.3) | 17 (46.0) | 17 (46.0) | 17 (46.0) | ||

| Occluded segment | 50 (24.9) | 10 (27.0) | 9 (24.3) | 10 (27.0) | ||

| Distal cap | 72 (35.8) | 10 (27.0) | 11 (29.7) | 10 (27.0) | ||

| Main vessel | ||||||

| Reference diameter, mm | 2.91±0.34 | 3.01±0.42 | .20 | 2.99±0.39 | 3.01±0.42 | .88 |

| Occlusion length, mm | 27.4±19.3 | 27.1±16.9 | .92 | 25.3±15.7 | 27.1±16.9 | .52 |

| Lesion length, mm | 41.0±23.3 | 43.9±23.4 | .51 | 39.7±23.1 | 43.9±23.4 | .61 |

| MLD post, mm | 2.59±0.57 | 2.72±0.51 | .24 | 2.72±0.46 | 2.72±0.51 | .99 |

| Stenosis post, % | 10.2±16.0 | 10.1±7.2 | .97 | 7.9±7.1 | 10.1±7.2 | .16 |

| Side branch | ||||||

| Reference diameter, mm | 2.30±0.29 | 2.53±0.38 | < .01 | 2.51±0.42 | 2.53±0.38 | .84 |

| MLD pre, mm | 1.41±0.73 | 0.79±0.44 | < .01 | 0.92±0.69 | 0.79±0.44 | .26 |

| Stenosis pre, % | 38±31 | 68±16 | < .01 | 64±22 | 68±16 | .22 |

| MLD post, mm | 1.72±0.60 | 2.20±0.62 | < .01 | 1.92±0.71 | 2.20±0.62 | .11 |

| Stenosis post, % | 25±22 | 13±16 | < .01 | 24±21 | 13±16 | .03 |

CTO, coronary chronic total occlusion; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; MLD, minimal lumen diameter; RCA, right coronary artery.

The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or No. (%).

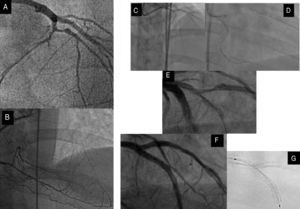

The procedural characteristics are summarized in Table 3. Recanalization techniques were similar between groups, with a predominance of antegrade techniques in both groups (78.6% vs 78.4%; P=ns). In the complex group, we observed a higher incidence of dissection affecting the bifurcation (48.6% vs 25.9%; P < .05) (Figure 3). Procedural metrics (contrast volume, radiation dose, and fluoroscopy time) were lower in the simple group.

Procedural Data

| Overall cohort | Propensity cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple (n=201) | Complex (n=37) | P | Simple (n=37) | Complex (n=37) | P | |

| Femoral access | 161 (80.1) | 28 (75.7) | .54 | 28 (75.7) | 28 (75.7) | > .99 |

| Successful crossing technique | .88 | .37 | ||||

| AWE | 125 (62.2) | 22 (59.5) | 19 (51.4) | 22 (59.5) | ||

| ADR | 33 (16.4) | 7 (18.9) | 8 (21.6) | 7 (18.9) | ||

| RWE | 21 (10.5) | 5 (13.5) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (13.5) | ||

| RDR | 22 (10.9) | 3 (8.1) | 7 (18.9) | 3 (8.1) | ||

| Number of guidewires used | 3.1±1.7 | 3.3±2.5 | .57 | 2.8±1.4 | 3.3±2.5 | .38 |

| Dissection affecting bifurcation | 52 (25.9) | 18 (48.6) | < .05 | 16 (43.2) | 18 (48.6) | .79 |

| Baseline wiring of the SB | 146 (72.6) | 33 (89.2) | < .05 | 32 (86.5) | 33 (89.2) | > .99 |

| Diameter of largest stent, mm | 3.01±0.37 | 3.03±0.40 | .69 | 3.06±0.47 | 3.03±0.40 | .78 |

| Stent length, mm | 47.5±24.9 | 48.6±22.8 | .80 | 47.8±26.8 | 48.6±22.8 | .77 |

| Type of stent | < .01 | .01 | ||||

| DES | 149 (74.1) | 36 (97.3) | 28 (75.7) | 36 (97.3) | ||

| BVS | 52 (25.9) | 1 (2.7) | 9 (24.3) | 1 (2.7) | ||

| Use of IVUS/OCT | 51 (25.4) | 9 (24.3) | .90 | 10 (27.0) | 9 (24.3) | > .99 |

| Contrast volume, mL | 326±113 | 367±111 | < .05 | 301±103 | 367±111 | < .01 |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 47.1±26.7 | 61.2±27.3 | < .05 | 47.7±28.9 | 61.2±27.7 | .04 |

| DAP, Gy/cm2 | 328.7±255.7 | 452.8±208.1 | < .05 | 354.1±303.7 | 452.8±208.1 | .04 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor at discharge | .42 | .65 | ||||

| Clopidogrel | 105 (52.2) | 22 (59.5) | 21 (56.8) | 22 (59.5) | ||

| Prasugrel or ticagrelor | 96 (47.8) | 15 (40.5) | 16 (43.2) | 15 (40.5) | ||

ADR, antegrade dissection-reentry; AWE, antegrade wire escalation; BVS, bioresorbable vascular scaffold; DAP, dose area product; DES, drug eluting-stent; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; OCT, optical coherence tomography; RDR, retrograde dissection-reentry; RWE, retrograde wire escalation; SB, side branch.

The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or No. (%).

Left anterior descending artery CTO with a significant diagonal branch in the proximal cap (A) and distal filling by collaterals from the RCA (B). C: retrograde approach through a septal channel. D: retrograde guidewire directly crossed to the true lumen and introduced into the guide catheter. E: after predilation, an important dissection crossing bifurcation site was observed. F: this fact, together with the existence of a large lesion in the SB, dictated the strategy and a minicrush was performed with a good angiographic result. G: assessment of the enhancement stent visualization. CTO, coronary chronic total occlusion; RCA, right coronary artery; SB, side branch.

Regarding the type of 2-stent technique, T-stenting was performed in 17 (45.9%) patients, minicrush in 10 (27%), culotte technique in 9 (24.3%), and V-stenting in 1 (2.7%) patient.

Technical success of CTO was achieved in all patients. Bifurcation technical success was 94.5% in the simple and 97.3% in the complex groups, respectively (P=.48). In all cases, bifurcation technical failure was due to a TIMI flow at the SB < 3 and the SBs were mainly located in the occluded segment or in the distal cap (91.7%). Procedural success was also similar between groups (85.6% vs 81.1%; P=.49).

In the group of patients excluded due to the impossibility to wire the SB, TIMI flow at the SB was < 3 in 79.3% of them.

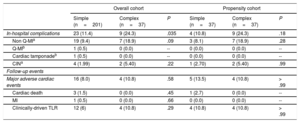

Unadjusted Analysis of In-hospital and Follow-up OutcomesThe incidence of procedural complications was higher in the complex group (24.3% vs 11.4%; P < .05). In this group, 7 patients had a non-Q periprocedural MI and 2 had contrast-induced nephropathy, while in the simple group 19 patients had a non-Q periprocedural MI, another had perforation with cardiac tamponade and early stent thrombosis 3 days later, and 4 developed contrast-induced nephropathy (Table 4).

In-hospital and Follow-up Outcomes

| Overall cohort | Propensity cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple (n=201) | Complex (n=37) | P | Simple (n=37) | Complex (n=37) | P | |

| In-hospital complications | 23 (11.4) | 9 (24.3) | .035 | 4 (10.8) | 9 (24.3) | .18 |

| Non Q-MIa | 19 (9.4) | 7 (18.9) | .09 | 3 (8.1) | 7 (18.9) | .28 |

| Q-MIb | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | -- | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| Cardiac tamponadeb | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | -- | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| CINa | 4 (1.99) | 2 (5.40) | .22 | 1 (2.70) | 2 (5.40) | .99 |

| Follow-up events | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac events | 16 (8.0) | 4 (10.8) | .58 | 5 (13.5) | 4 (10.8) | > .99 |

| Cardiac death | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | .45 | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| MI | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | .66 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| Clinically-driven TLR | 12 (6) | 4 (10.8) | .29 | 4 (10.8) | 4 (10.8) | > .99 |

CIN, contrast-induced nephropathy; MI, myocardial infarction; TLR, target lesion revascularization.

The data are expressed as No. (%).

Among the 29 excluded patients (no wiring the SB despite the operator's intention), the procedural complications rate was 27.6%: 7 patients (24.1%) developed a non-Q MI and another (3.4%) had a cardiac tamponade.

Follow-up was available for 236 patients (99%). The median follow-up was 25 months (interquartile range, 14-38). There were no significant differences in the unadjusted rates of events between groups. In particular, the MACE rate was 8% in the simple group and 10.8% in the complex group (P=.58) (Table 4). Kaplan-Meier curves of MACE-free survival at 3 years of follow-up are shown in Figure 4. There was a trend toward lower MACE-free survival in the complex group (80.1% vs 69.8%, P=.08).

Propensity Score-matched AnalysisAfter propensity score matching, a total of 37 matched pairs were generated. After adjustment, all covariates showed standardized mean differences within the 10% cutoff, except dissection affecting bifurcation (10.7%) (Figure 2). The propensity score model showed the appropriate goodness-of-fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow P=.22). There were no differences in the clinical, angiographic, or procedural characteristics in the propensity score-matched population (Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3). Technical and procedural success were similar in the simple and complex groups (89.2% vs 97.3%; P=ns; and 83.8% vs 83.8%; P=ns). However, a complex strategy was associated with increased fluoroscopy time, X-ray dose, and contrast volume (Table 3). The incidence of periprocedural complications was 10.8% in the simple group and 24.3% in the complex group (P=.18) (Table 4).

After a median follow-up of 25 months, MACE rates did not differ between groups in the propensity score-matched cohort (13.5% vs 10.8%; P > .99) (Table 4). As in the overall analysis, MACE-free survival at 3 years was similar (78.3% vs 69.8%; P=.28) (Figure 5).

DISCUSSIONThe main findings of our study are as follows: a) Bifurcation lesions are found in approximately one fourth of CTO PCIs. b) Bifurcation lesions in CTO can be approached similarly to regular bifurcation lesions, for which provisional stenting is considered the technique of choice. However, the SB stenting rate seems to be higher (15.6%) than in previous series of provisional stenting for regular bifurcation lesions.1,4,5c) On adjusted analysis, there were no differences in mid-term outcomes between the simple and complex strategies.

The treatment of bifurcation lesions has been widely studied, and ample evidence and recommendations exist in non-CTO bifurcation PCI.1–8 However, there are few data on the optimal management when bifurcation lesions are found in the recanalization process of a CTO. Various studies have reported that this association is frequent (from 47% to 26.5%) and is linked to more periprocedural complications than CTO-PCI without adjacent significant SB.13,16,17

Wiring of the SB at baseline has been described as a predictor of procedural success in non-CTO bifurcation lesions.18 However, in CTO-PCI, this maneuver can be difficult, mostly when the SB is located within the occluded segment or at the distal cap. In this study, the SB could not be accessed in 11% of the patients despite the operator's intention (Figure 1), a rate much higher than that reported in non-CTO bifurcation lesions.19 During CTO recanalization, the induction of dissections is frequent, which can jeopardize further attempts to access the SB.20

No randomized trial or propensity score-adjusted comparison has been published evaluating the treatment strategy of bifurcations in this scenario. The need to prevent major SB loss together with procedural complexity and duration may influence the type of treatment applied.

In our previous study,13 when SB wiring was feasible, a simple approach was the strategy used in most of the patients and the use of 2-stent techniques was strongly associated with the presence of important dissections affecting the bifurcation site (Figure 3). In a series of 244 CTOs with bifurcation lesions, Galassi et al.17 reported a higher incidence of the 2-stent treatment (approximately 50%), whereas Chen et al.16 treated 25% of the bifurcations located immediately proximal to the occlusion and 7% of those located at the distal cap with the complex strategy.

The present study is the first to compare a simple vs complex approach in patients with bifurcation lesions in CTO using a solid statistical adjustment technique. In the overall cohort, a simple approach was the treatment chosen for most of the patients (84.4%) with similar technical and procedural success rates and incidence of MACE on follow-up. These findings were confirmed by our adjusted analysis. Additionally, a complex (2-stent) strategy was associated with worse procedural metrics, as previously reported in non-CTO bifurcations PCI.4,8,21 This finding is especially relevant in the CTO setting, where the recanalization procedure is complex and time-consuming per se. Therefore, in light of these results, the complex strategy should not be systematically recommended in this particular type of lesion. However, the 2-stent technique may be considered when a large SB shows diffuse disease or long dissection and when the operator considers rewiring to be difficult after main vessel stent implantation.

Another important consideration is the 2-stent technique chosen in this particular scenario. The small number of patients who underwent this strategy in our series does not allow us to draw definitive conclusions. However, if a complex strategy is planned, we believe that it seems reasonable to first secure the SB stenting, and then to proceed to main vessel stent implantation.

LimitationsThe present study has several limitations. First, this is not a randomized controlled trial. Despite the propensity score matching, we cannot rule out the effect of residual confounders. Second, the number of patients treated with the complex strategy was limited compared with those treated with the simple strategy and therefore the number of pairs generated was small, limiting the statistical power of the study. Therefore, the lack of difference in clinical outcomes between groups might reflect a type II error. Third, angiographic analyses were not performed by a core laboratory but by an experienced interventional cardiologist. Finally, our findings might not be directly extrapolable to other institutions without interventional cardiologists experienced in CTO-PCI.

ConclusionsBifurcation lesions in the context of a CTO-PCI are a frequent finding and represent a challenging situation. In our experience, provisional stenting was the chosen strategy in most patients without significant differences in technical and procedural success rates, or the incidence of MACE during follow-up compared with patients treated with the complex strategy. These findings were confirmed in the propensity score-matched population, and the procedural metrics (contrast volume, fluoroscopy time, and radiation dose) all favored the simple approach. Therefore, the simple approach can be recommended in most of these lesions. However, these results require confirmation in larger and randomized studies.

- –

Provisional SB stenting is the current preferred strategy for the percutaneous treatment of bifurcation lesions. However, it is unclear whether this recommendation is applicable to bifurcation lesions in the context of a CTO.

- –

When wiring of the SB was technically feasible, there were no differences between the simple and complex strategies regarding immediate and mid-term outcomes after propensity score matching analysis. Therefore, in this particular setting, provisional stenting could be the recommended treatment in most bifurcation lesions.

S. Ojeda, J. Suárez de Lezo and M. Pan have received minor lectures fees from Abbott. L. Azzalini reports receiving honoraria from Guerbet and serves as research support for ACIST medical systems.