To the Editor,

Although electric scalpels or electrosurgery have provided a major advance in surgical procedures in general, they are a source of electromagnetic interference that may have an impact on patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices, especially when these are used in monopolar modality. This is the most common modality used except in the case of microsurgery or ophthalmic surgery procedures, in which bipolar electrocautery is more common. Thus, problems can arise such as oversensing and pacing inhibition, irreversible damage to the generator, device reprogramming or resetting, inappropriate defibrillator therapy due to oversensing false tachyarrhythmias or even, in rare cases, the induction of potentially fatal arrhythmias.1 In monopolar electrosurgery and electrocautery, the electric current is applied through the tip of the electric scalpel to the area of interest and from this point flows through the patient's body until reaching the large surface area return electrode, that is, the dispersive pad on the patient's skin.

We describe two cases in which malignant ventricular arrhythmias occurred in association with electrocautery during cardiovascular implantable electronic devices revision surgical procedures.

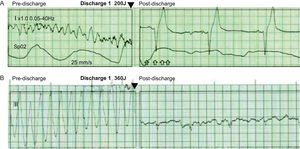

Case 1 was a 69-year-old man with hypertension and preserved ventricular function, who was admitted for elective replacement of a pacemaker generator which had reached its replacement date. For 9 years, he had a normally functioning dual-chamber pacemaker system (Vitatron Vita 2 model 830), with active fixation electrodes positioned in the right atrial appendage (Vitatron Crystalline ICL08JB-53cm) and in the right ventricular septal wall (Vitatron Crystalline ICL08B-58cm) (Figure 1). Before surgery, the patient's own heart rate was confirmed at 60bpm, with excellent sensing and stimulation parameters. To perform the procedure, the device was reprogrammed to VVI mode at 40bpm in bipolar configuration. We used an electrocautery system (Valleylab Force FX) programmed for cutting and coagulation in monopolar mode (cutting power, 25 W; coagulation power, 35 W) with a dispersive pad positioned on the outside of the patient's right thigh. After incision with a conventional scalpel, electrocautery was used in monopolar mode throughout the procedure. During initial dissection of the subcutaneous tissue, and coinciding with the electrocoagulation of an arteriole at a pulse of no more than 3s, the patient suddenly lost consciousness with ventricular fibrillation rhythm documented on the monitor. This was immediately treated using an external biphasic defibrillator to deliver a nonsynchronized shock of 200 J, converting to sinus bradycardia at 42bpm (Figure 2). At the time of the event, the generator was still within the fibrous capsule and connected to the electrodes. The patient regained consciousness without sequelae and the generator replacement procedure was completed without further incident. We checked the sensing and stimulation parameters of the electrodes with the new generator implanted, which were similar to those observed before the procedure. No incidents were documented during post-discharge follow-up.

Figure 1. Posteroanterior chest radiograph of the patients in case 1 (A) and case 2 (B) after the first implantation.

Figure 2. Rate trace of the patients in case 1 (A) and case 2 (B) from the external monitor-defibrillator during an induced malignant ventricular arrhythmia episode (left) and immediately after the shock applied (right).

Case 2 was a 74-year-old man with a single-chamber pacemaker (Identity ADx SR 5180 and a Tendril 1888TC/58 pacing lead; St Jude Medical) (Figure 1). The patient had hypertension with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction. He was admitted in order to upgrade to an implantable cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator for primary prevention. The device was programmed to VVI mode at 40bpm in bipolar configuration; the patient's own heart rate was 50bpm with excellent parameters. We used the same equipment as described in case 1, using the same electrocautery system in bipolar mode. When the fibrous capsule covering the generator was opened to release it—while applying short electrocautery pulses to the surface of the generator in contact with the fibrous tissue—the patient reported dizziness with very rapid wide QRS-complex regular tachycardia (Figure 2), which was documented on the monitor, immediately followed by syncope. The tachycardia was terminated with a biphasic shock of 360J. The procedure continued without further incident while contact between the tip of electric scalpel and the implanted generator and lead was avoided. One lead was implanted in the right atrium, 1 in the left ventricle and 1 for defibrillation in the right ventricular apex. The permanent pacemaker lead was left in situ with a silicone end-cap. No further incidents have been documented during patient follow-up.

In the cases presented, the mechanism underlying the induction of ventricular fibrillation could have been due to the continuous transmission—through the ventricular electrode to the interface with the myocardium—of the electrocautery radiofrequency pulses applied to the surrounding tissue or the pacemaker generator itself,2 although long pulses were not applied and it was programmed in bipolar mode in both cases. The cases presented raise the issue of possible complications with the use of electrocautery, especially in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Although the frequency of complications is low,2 they are potentially fatal, and therefore a number of precautionary measures should be applied, including placing the dispersive pad as far from the generator as possible, reducing the energy pulses to less than 5s’ duration and, as a matter of course and in all cases, having continuous monitoring and advanced resuscitation equipment available during the procedure.3 Nevertheless, as long as the risk of bleeding is not especially high, a cold scalpel, with careful dissection followed by complete homeostasis, may be sufficient, thus completely avoiding the use of the electric scalpel in many of these interventions.

Corresponding author: maapalomares@secardiologia.es