Contrasting data have been reported on bivalirudin as an anticoagulation strategy during percutaneous coronary interventions, offering theoretical benefits on bleeding complications but raising concerns on a potential increase in the risk of stent thrombosis. We performed an updated meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of bivalirudin compared with unfractionated heparin in patients undergoing percutaneous interventions for acute coronary syndromes.

MethodsLiterature archives and main scientific sessions were scanned. The primary efficacy endpoint was 30-day overall mortality. Secondary endpoints were stent thrombosis and major bleeding. A prespecified analysis was conducted according to clinical presentation.

ResultsTwelve randomized trials were included, involving 32 746 patients (52.5% randomized to bivalirudin). Death occurred in 1.8% of the patients, with no differences between bivalirudin and heparin (odds ratio = 0.91; 95% confidence interval, 0.77-1.08; P = .28; P for heterogeneity = .41). Similar results were obtained for patients with non—ST-segment elevation and in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. A significantly higher rate of stent thrombosis was observed with bivalirudin (odds ratio = 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.83; P = .008; P for heterogeneity = .09). Bivalirudin was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of major bleeding (odds ratio = 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.54-0.75; P < .00001; P for heterogeneity < .0001), which, however, was related to the differential use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (r = −0.02 [−0.033 to –0.0032]; P = .02) and did not translate into survival benefits.

ConclusionsIn patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions, bivalirudin is not associated with a reduction in mortality compared with heparin but does increase stent thrombosis. The reduction in bleeding complications observed with bivalirudin does not translate into survival benefits but is rather influenced by a differential use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

Keywords

Increasing complexity in patients admitted for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is rendering more and more challenging the management of antithrombotic therapies, requiring continuous balancing between the risks of bleeding and thrombotic complications.1–3

Bivalirudin has been proposed as an alternative strategy to unfractionated heparin (UFH) for anticoagulation during percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), offering several theoretical advantages including activity against clot-bound thrombin, inhibition of thrombin-induced platelet activation, short plasma half-life, and a lower dependence on renal clearance.4

Moreover, the first studies suggested that bivalirudin could provide similar effectiveness to UFH, but with a significant reduction in bleeding complications.5,6 However, these trials did not consider patients with ACS, in whom the balance between bleeding and ischemic events is more complex.

In these settings, more recent clinical trials and pooled analyses7–9 have suggested that bivalirudin could be associated with an even higher risk of stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction, while offering no advantage in the reduction of hemorrhagic complications, besides raising the hypothesis that the differences in bleedings observed with bivalirudin could be affected by access-site bleedings or by greater use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa) inhibitors, in association with UFH.

Therefore, the MATRIX trial10 has been conducted, comparing bivalirudin with UFH in ACS patients, randomly assigned to undergo PCI by either the radial or femoral route, showing no advantage from the use of bivalirudin in terms of ischemic, bleeding or combined endpoints. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to perform the most comprehensive meta-analysis to evaluate the safety and efficacy of bivalirudin compared with UFH during PCI, including the data from most recent randomized trials in the setting of ACS.

METHODSEligibility and Search StrategyThe literature was scanned by formal searches of electronic databases (MEDLINE, Cochrane and EMBASE) for clinical studies and scientific session abstracts, searched on the TCT,11 EuroPCR,12 ACC,13 AHA,14 and ESC,15 websites for oral presentations and/or expert slide presentations from January 1990 to September 2015. The following keywords were used: “bivalirudin and acute coronary syndrome” or “bivalirudin versus heparin” or “bivalirudin and trial”. No language restrictions were enforced.

Data Extraction and Validity AssessmentData were independently abstracted by 2 investigators. If the data were incomplete or unclear, authors were contacted, when possible. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data were managed according to the intention-to-treat principle.

Outcome MeasuresThe primary efficacy endpoint was overall mortality at 30 days of follow-up. The secondary endpoint was the occurrence of stent thrombosis at 30 days. The primary safety endpoint was the occurrence of major bleedings (according to per protocol definition) within the first 30 days from randomization. A prespecified meta-analysis was conducted according to patients’ presentation (non—ST-segment elevation ACS or ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI]).

Data AnalysisThe statistical analysis was performed using the Review Manager 5.23 freeware package, SPSS 17.0 statistical package. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were used as summary statistics. The pooled OR was calculated by using a fixed effect model. The Breslow-Day test was used to examine the statistical evidence of heterogeneity across the studies (P < .1). A random-effect model was also applied to confirm our results (DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model). The study quality was evaluated by the same 2 investigators according to a score, which, as previously described,16 was expressed on an ordinal scale, allocating 1 point for the presence of each of the following: a) statement of objectives; b) explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria; c) description of the intervention; d) objective means of follow-up; e) availability of data on endpoint events; f) power analysis; g) description of statistical methods; h) multicenter design; i) discussion of withdrawals, and j) details on medical therapy. A meta-regression analysis was carried out to evaluate the following: the relationship between the benefits in mortality from bivalirudin vs UFH and patients’ risk profile (as log of the OR for mortality in the control group); the impact on mortality of the reduction in bleeding complications with bivalirudin (as log of the OR for bleeding events in the bivalirudin vs control groups); the bleeding reduction with bivalirudin and patients’ risk profile (as log of the OR for bleeding events in the control group). The study was performed in compliance with the Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.17

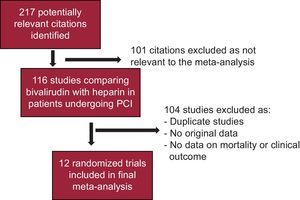

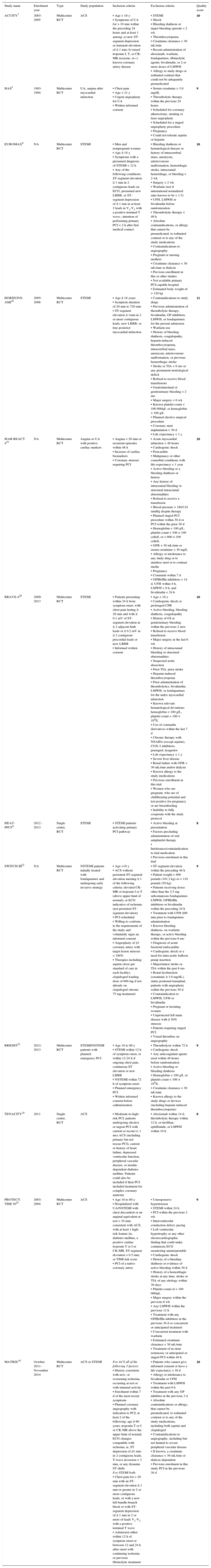

RESULTSEligible StudiesA total of 12 randomized clinical trials5,7,8,10,18–25 were finally included, for a total population of 32 746 patients (Figure 1). One study was excluded as it included only 24% of non—ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients.26 Detailed characteristics of included trials are shown in Table 1. Among them, 17 189 patients (52.5%) were randomized to bivalirudin and 15 557 patients (47.5%) to UFH with or without planned GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors. Preprocedural fondaparinux was administered in 100% of patients in 1 trial.22 As shown in Table 2, the mean age was 61.9 ± 2.1 years, with 19.5% of diabetics and 13.9% with renal failure. Use of GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors was 15.1% in the bivalirudin group (excluded in 3 trials5,19,25 and 49.7% in the UFH group (planned 100% in 5 trials).7,18,19,23,25 Six trials were conducted in STEMI patients,8,10,13,15,16,18 while 8 trials focused on patients with ACS (unstable angina [UA]/NSTEMI).5,7,10,19,22-25. Follow-up data were collected at 30 days in 10 trials,7,8,10,18–21,23–25 in-hospital in 2 trials,5,22 and in 1 follow-up was performed 48 hours after discharge.25

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Study name | Enrolment year | Type | Study population | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACUITY7 | 2003-2005 | Multicenter RCT | ACS | • Age > 18 y • Symptoms of UA for > 10 min within the preceding 24 hours and at least 1 among: a) new ST-segment depression or transient elevation of ≥ 1 mm; b) raised troponin I, T, or CK-MB isozyme, or c) known coronary artery disease | • STEMI • Shock • Bleeding diathesis or major bleeding episode < 2 wk • Thrombocytopenia • Creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min • Recent administration of abciximab, warfarin, fondaparinux, fibrinolytic agents, bivalirudin, or 2 or more doses of LMWH • Allergy to study drugs or iodinated contrast that could not be adequately premedicated | 10 |

| HAS5 | 1993-1994 | Multicenter RCT | UA, angina after myocardial infarction | • Chest pain • Age > 21 y • Urgent angioplasty for UA • Written informed consent | • Serum creatinine > 3.0 mg/dL • Thrombolytic therapy within the previous 24 hours • Scheduled for coronary atherectomy, stenting or laser angioplasty • Scheduled for a staged angioplasty procedure • Pregnancy • Could not tolerate aspirin or heparin | 9 |

| EUROMAX8 | NA | Multicenter RCT | STEMI | • Men and nonpregnant women • Age ≥ 18 y • Symptoms with a presumed diagnosis of STEMI < 12 h • Any of the following conditions: ST-segment elevation ≥ 1 mm in 2 contiguous leads on ECG, presumed new LBBB, or ST-segment depression of ≥ 1 mm in at least 2 leads in V1-V3 with a positive terminal T wave.; intention of performing primary PCI < 2 h after first medical contact. | • Bleeding diathesis or hematological disease or history of intracerebral mass, aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, hemorrhagic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, or bleeding < 2 wk • Surgery < 2 wk • Warfarin (not if international normalized ratio known to be < 1.5) • UFH, LMWH or bivalirudin before randomization • Thrombolytic therapy < 48 h • Absolute contraindications, or allergy that cannot be premedicated, to iodinated contrast or to any of the study medications • Contraindications to angiography • Pregnant or nursing mothers • Creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min or dialysis • Previous enrollment in this or other studies • Not available primary PCI-capable hospital • Estimated body weight of > 120 kg | 10 |

| HORIZONS-AMI18 | 2005-2008 | Multicenter RCT | STEMI | • Age ≥ 18 years • Symptom duration of 20 min to 720 min • ST-segment elevation ≥ 1mm in 2 or more contiguous leads, new LBBB, or true posterior myocardial infarction | • Contraindications to study drugs • Previous administration of thrombolytic therapy, bivalirudin, GP inhibitors, LMWH, or fondaparinux for the present admission • Warfarin use • History of bleeding diathesis, coagulopathy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, intracerebral mass, aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, or previous hemorrhagic stroke • Stroke or TIA < 6 mo or any permanent neurological deficit • Refusal to receive blood transfusions • Gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding < 2 mo • Major surgery < 6 wk • Known platelet count < 100 000/μL or hemoglobin < 100 g/L • Planned elective surgical procedure • Coronary stent implantation < 30 d • Life expectancy < 1 y | 11 |

| ISAR-REACT 419 | NA | Multicenter RCT | Angina or UA with positive cardiac markers | • Angina > 20 min or recurrent episodes within 48 h • Increase of cardiac biomarkers • Coronary stenosis requiring PCI | • Acute myocardial infarction < 48 hours • Cardiogenic shock • Pericarditis • Malignancy or other comorbid conditions with life expectancy < 1 year • Active bleeding or a bleeding diathesis or history • Any history of intracranial bleeding or structural intracranial abnormalities • Refusal to receive a transfusion • Blood pressure > 180/110 mmHg despite therapy • Planned staged PCI procedure within 30 d or PCI within the prior 30 d • Hemoglobin < 100 g/L, platelet count < 100 × 109 cells/L or > 600 × 109 cells/L • GFR < 30 mL/min or serum creatinine > 30 mg/L • Allergy or intolerance to any study drug or to stainless steel or to contrast media • Pregnancy • Coumarin within 7 d • GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors < 14 d, UFH within 4 h, LMWH < 8 h, and bivalirudin < 24 h | 10 |

| BRAVE-420 | 2009-2013 | Multicenter RCT | STEMI | • Patients presenting within 24 h from symptom onset, with chest pain lasting ≥ 20 min and with ≥ 0.1 mV of ST-segment elevation in ≥ 2 adjacent limb leads or ≥ 0.2 mV in ≥ 2 contiguous precordial leads or new LBBB • Informed written consent | • Age < 18 y • Cardiogenic shock or prolonged CPR • Active bleeding, bleeding diathesis, coagulopathy • History of GI or genitourinary bleeding within the previous 2 mos • Refusal to receive blood transfusion • Major surgery in the last 6 wk • History of intracranial bleeding or structural abnormalities • Suspected aortic dissection • Prior TIA, prior stroke • Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia • Prior administration of thrombolytics, bivalirudin, LMWH, or fondaparinux for the index myocardial infarction • Known relevant hematological deviations: hemoglobin < 100 g/L, platelet count < 100 × 109/L • Use of coumadin derivatives within the last 7 d • Chronic therapy with NSAIDs (except aspirin), COX-2 inhibitors, prasugrel, ticagrelor • Life expectancy < 1 y • Severe liver disease • Renal failure with GFR < 30 mL/min and/or dialysis • Known allergy to the study medications • Previous enrollment in this trial • Women who are pregnant, who are of childbearing potential and test positive for pregnancy or are breastfeeding • Inability to fully cooperate with the study protocol | 10 |

| HEAT-PPCI21 | 2012 - 2013 | Single center, RCT | STEMI | • STEMI patients activating primary PCI pathway | • Active bleeding at presentation • Factors precluding administration of oral antiplatelet therapy • Intolerance/contraindication to trial medication • Previous enrolment in this trial | 8 |

| SWITCH III22 | NA | Multicenter RCT | NSTEMI patients initially treated with fondaparinux and undergoing early invasive strategy | • Age >18 y • ACS without persistent ST-segment elevation meeting ≥ 1 of the following criteria: elevated CK-MB or troponin I or T (above upper limit of normal), or ECG indicative of ischemia (not persistent ST-segment elevation) • PCI scheduled • Willing to conform to the requirements of the study and voluntarily signs an informed consent • Angioplasty of ≥1 coronary artery with target lesion stenosis < 100% • Therapies including aspirin (dose per standard of care in each facility), clopidogrel loading dose of 600 mg if not already on clopidogrel chronic 75 mg treatment) | • ST-segment elevation within the preceding 48 h • Patient weight > 400 pounds (181.2 kg) or < 110 pounds (50 kg) • Patients receiving doses other than the 2.5 mg subcutaneous fondaparinux LMWH, GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors or bivalirudin within the preceding 24 h • Treatment with UFH ≤90 min prior to fondaprinux administration • Known bleeding diathesis, on warfarin therapy, or active bleeding within the previous 6 mo • Diagnosis of acute bacterial endocarditis • Cardiogenic shock or a need for intra-aortic balloon pump insertion • Major/minor stroke or TIA within the past 6 mo • Renal dysfunction (creatinine ≥ 3.0 mg/dL), status postrenal transplant, patients with angioplasty within the previous 30 d • Contraindication to LMWH, UFH or bivalirudin • Pregnant or lactating women • Unprotected left main disease with ≥ 50% stenosis • Patients requiring staged PCI • Visual thrombus on angiography | 9 |

| BRIGHT23 | 2012- 2013 | Multicenter RCT | STEMI/NSTEMI patients with planned emergency PCI | • Age 18 to 80 y • STEMI within 12 h of symptom onset, or within 12-24 h if ongoing chest pain, continuous ST elevation or new LBBB • NSTEMI within 72 h of symptom onset • Planned emergency PCI • Written informed consent before catheterization | • Thrombolysis within 72 h • Cardiogenic shock • Any anticoagulant agents used within 48 hours before randomization • Active bleeding or bleeding diathesis • Hemoglobin < 100 g/L or platelet count < 100 × 109/L • Creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min • Known allergy to the study drugs or devices (including heparin induced thrombocytopenia) | 9 |

| TENACITY24 | 2011 | Single center, RCT | ACS | • Moderate-to-high-risk PCI: patients undergoing elective or urgent PCI with current or recent (< 1 mo) ACS (including primary but not rescue PCI), current or history of heart failure, depressed ventricular function, peripheral vascular disease, or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Patients could also be included if their PCI included treatment for complex coronary anatomy | • Abciximab within 14 d, thrombolytic therapy within 12 h, or tirofiban, eptifibatide, or LMWH within 10 h | 8 |

| PROTECT-TIMI 3025 | 2003-2004 | Multicenter RCT | ACS | • Age 18 to 80 y • Hospitalized with UA/NSTEMI with chest discomfort or an anginal equivalent at rest > 10 min; consistent with ACS, with at least 1 high-risk feature (ie, diabetes mellitus, a positive cardiac troponin T or I or CK-MB, ST-segment deviation > 0.5 mm, or TIMI risk score • PCI of a native coronary artery | • Unresponsive hypertension • STEMI within 24 h • PCI within the previous 2 wk • Intraventricular conduction defect, pacing • Left ventricular hypertrophy or any other electrocardiographic finding that could make continuous ECG monitoring uninterpretable • Cardiogenic shock • History of a bleeding diathesis or evidence of active bleeding within 30 d • History of a hemorrhagic stroke at any time, stroke or TIA of any etiology within 30 days • Platelet count of < 100 000/μL • Major surgery within the previous 6 wk • Any LMWH within the previous 12 h • Treatment with any GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors in the previous 30 d or concurrent or anticipated treatment • Concurrent treatment with warfarin • Estimated creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min • Treatment of in-stent restenosis; or anticipated or staged PCI within 48 h | 9 |

| MATRIX10 | October 2011-November 2014 | Multicenter RCT | ACS or STEMI | For ACS all of the following 3 factors: • History consistent with new, or worsening ischemia, occurring at rest or with minimal activity • Enrolment within 7 d of the most recent symptoms • Planned coronary angiography with indication to PCI; at least 2 of the following: age ≥ 60 years; troponin T or I or CK-MB above the upper limit of normal; ECG changes compatible with ischemia, ie, ST depression of ≥1 mm in 2 contiguous leads, T-wave inversion > 3 mm, or any dynamic ST shifts For STEMI both: • Chest pain for > 20 min with an ST-segment elevation ≥ 1 mm or greater in 2 or more contiguous leads, or with a new left bundle-branch block or with ST-segment depression of ≥ 1 mm in 2 or more of leads V1-V3 with a positive terminal T wave • Admission either within 12 h of symptom onset or between 12 and 24 h after onset with continuing ischemia or previous fibrinolytic treatment | • Patients who cannot give informed consent or have a life expectancy < 30 d • Allergy or intolerance to bivalirudin or UFH • Treatment with LMWH within the past 6 h • Treatment with any GP inhibitor in the previous 3 d • Absolute contraindications or allergy, that cannot be premedicated, to iodinated contrast or to any of the study medications, including both aspirin and clopidogrel • Contraindications to angiography, including but not limited to severe peripheral vascular disease • If known, a creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min or dialysis dependent • Previous enrolment in this study PCI in the previous 30 d | 10 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CK-MB, creatine kinase-myocardial band; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; CRP, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECG, electrocardiogram; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; GP, glycoprotein; GPIIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; INR, international normalized ratio; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LMWH, low-molecular weight heparin; NA, not available; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; NSTEMI, non—ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCT, randomized clinical trial; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischemic accident; TIMI, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction; UA, unstable angina; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

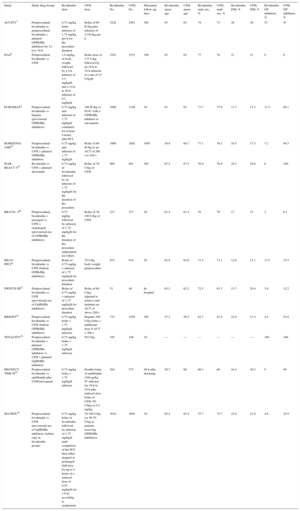

Clinical Features of Patients in Included Studies

| Study | Study drug design | Bivalirudin dose | UFH dose | Bivalirudin, No. | UFH, No. | Maximum follow-up, days | Bivalirudin, mean age | UFH, mean age | Bivalirudin, male sex, % | UFH, male sex, % | Bivalirudin, DM, % | UFH, DM, % | Bivalirudin, GP inhibitors, % | UFH, GP inhibitors, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACUITY7 | Periprocedural bivalirudin or periprocedural bivalirudin + planned GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors for 12-h to 18-h | 0.75 mg/kg bolus infusion of 1.75 mg/kg per h for the procedure duration | Bolus of 60 IU/kg plus infusion of 12 IU/kg per h | 5228 | 2561 | 365 | 63 | 63 | 74 | 73 | 28 | 28 | 53 | 97 |

| HAS5 | Periprocedural bivalirudin vs UFH | 1.0 mg/kg of body weight, followed by a 4-h infusion of 2.5 mg/kg/h and a 14-h to 20-h infusion of 0.2 mg/kg/h | Bolus dose of 175 U/kg followed by an 18-h to 24-h infusion at a rate of 15 U/kg/h | 2161 | 2151 | 180 | 63 | 62 | 77 | 78 | 21 | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| EUROMAX8 | Periprocedural bivalirudin vs heparin (provisional GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors) | 0.75 mg/kg and infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/h continued for at least 4 hours after PCI | 100 IU/kg or 60 IU with a GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor or enoxaparin | 1089 | 1109 | 30 | 61 | 62 | 73.7 | 77.6 | 11.7 | 15.3 | 11.5 | 69.1 |

| HORIZONS-AMI18 | Periprocedural bivalirudin vs UFH + planned GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors | 0.75 mg/kg and infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/h | Bolus of 60 IU/kg to an ACT of 200 s to 250 s | 1800 | 1802 | 1095 | 59.8 | 60.7 | 77.1 | 76.1 | 16.5 | 17.3 | 7.2 | 94.5 |

| ISAR -REACT 419 | Bivalirudin vs UFH + planned abciximab | 0.75 mg/kg of bivalirudin, followed by an infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/h for the duration of the procedure | Bolus of 70 U/kg of UFH | 860 | 861 | 365 | 67.5 | 67.5 | 76.9 | 76.8 | 28.3 | 29.8 | 0 | 100 |

| BRAVE- 420 | Periprocedural bivalirudin + prasugrel vs UFH + clopidogrel (provisional use of GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors) | 0.75 mg/kg, followed by infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/h for the duration of the procedure (adjustment for CKD) | Bolus of 70-100 U/kg of UFH | 271 | 277 | 30 | 61.4 | 61.4 | 76 | 79 | 17 | 15 | 3 | 6.1 |

| HEAT-PPCI21 | Periprocedural bivalirudin vs UFH (bailout GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors) | Bolus of 0.75 mg/kg + infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/h for procedure duration | 70 U/kg body weight preprocedure | 915 | 914 | 28 | 62.9 | 63.6 | 71.5 | 73.1 | 12.6 | 15.1 | 13.5 | 15.5 |

| SWITCH III22 | Periprocedural bivalirudin vs UFH (provisional use of GpIIb/IIIa inhibitors) | Bolus of 0.75 mg/kg + infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/h for procedure duration | Bolus of 60 U/kg, adjusted to achieve and maintain an ACT of above 200 s | 51 | 49 | In-hospital | 63.3 | 62.2 | 72.5 | 63.3 | 13.7 | 20.4 | 3.9 | 12.2 |

| BRIGHT23 | Periprocedural bivalirudin vs UFH (bailout GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors) | 0.75 mg/kg bolus + 1.75 mg/kg/h infusion | Heparin 100 U/kg bolus + additional dose if ACT < 200 s | 735 | 1459 | 365 | 57.3 | 58.2 | 82.7 | 81.9 | 22.9 | 21.4 | 4.4 | 52.8 |

| TENACITY24 | Periprocedural bivalirudin + planned GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors vs UFH + planned GpIIb/IIIa inhibitors | 0.75 mg/kg bolus + 1.75 mg/kg/h infusion | 50 U/kg | 185 | 198 | 30 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 100 | 100 |

| PROTECT-TIMI 3025 | Periprocedural bivalirudin vs eptifibatide plus UFH/enoxaparin | 0.75 mg/kg bolus + 1.75 mg/kg/h infusion | Double bolus of eptifibatide (180 μg/kg IV infusion for 18-h to 24-h plus reduced dose bolus of UFH (50 U/kg) or 0.5 mg/kg | 284 | 573 | 48 h after discharge | 59.7 | 60 | 68.3 | 66 | 44.4 | 36.5 | 0 | 99 |

| MATRIX10 | Periprocedural bivalirudin vs UFH (provisional use of GpIIb/IIIa inhibitors, bailout only in bivalirudin group) | 0.75 mg/kg bolus of bivalirudin, followed by infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/h until completion of the PCI, then either stopped or prolonged (full dose for up to 4 hours of a reduced dose of 0.25 mg/kg/h for > 6 h) according to assignment | 70-100 U/kg (or 50-70 U/kg in patients receiving GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors) | 3610 | 3603 | 30 | 65.4 | 65.4 | 75.7 | 75.7 | 22.6 | 21.8 | 4.6 | 25.9 |

ACT, activated clotting time; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; GP, glycoprotein; GPIIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; IV, intravenous; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

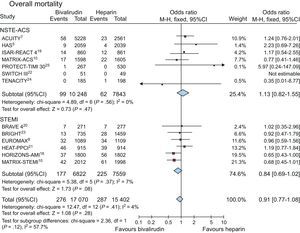

Data on overall mortality were available in 32 472 patients (99.1%). Death occurred in 563 (1.7%) of patients. As shown in Figure 2, no difference in mortality was observed between bivalirudin and UFH (1.6%, [276 of 17 070] vs 1.8% [287 of 15 402], OR = 0.91; 95%CI, 0.77-1.08; P = .28; P for heterogeneity = .41).

Similar results were obtained for patients with UA/NSTEMI (0.96%, [99 of 10 248] vs 0.8% [62 of 7843], OR = 1.13; 95%CI, 0.82-1.55; P = .47; P for heterogeneity = .56) and in STEMI (2.6% [177 of 6822] vs 3% [225 of 7559], OR = 0.84; 95%CI, 0.69-1.02; P = .08; P for heterogeneity = .37; P for interaction = .12).

No difference in mortality with bivalirudin was confirmed by applying a random-effect model to the analysis (OR = 0.91; 95%CI, 0.76-1.09; P = .31; P for heterogeneity = .41), with no difference in non—ST-segment elevation ACS and STEMI patients.

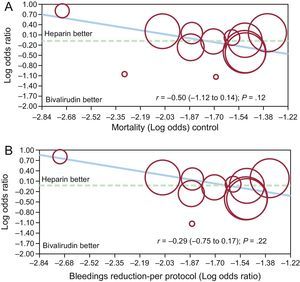

By meta-regression analysis no significant relationship was observed between benefits in mortality with bivalirudin compared with UFH, and patient risk profiles or the reduction in bleeding complications (r = −0.50 [−1.12 to 0.14]; P = .12) and (r = −0.29 [−0.75 to 0.17]; P = .22) (Figures 3A and 3B respectively). Lack of impact on survival for the reduction in bleeding complications was similarly observed among patients with UA/NSTEMI (r = −1.05[−2.5 to 0.40]; P = .16) and STEMI (r = −0.94[−1.19 to 3.08]; P = .39).

Fixed-effect meta-regression analyses for the risk (odds ratio) of mortality between bivalirudin and unfractionated heparin according to patients’ risk profile (A) or the reduction in major bleedings with bivalirudin (B). The size of the circle corresponds to the statistical weight of each study.

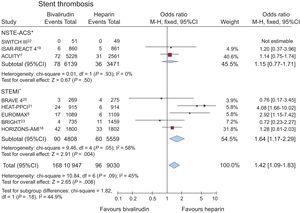

Data on stent thrombosis were available in 19977 patients (60.8%), out of 8 studies.7,8,13-18 Stent thrombosis occurred in 264 (1.3%) of patients. Bivalirudin significantly increased the risk of stent thrombosis (1.5% [168 of 10 947] vs 1% [96 of 9030], OR = 1.42; 95%CI, 1.09-1.83; P = .008; P for heterogeneity = .09), as shown in Figure 4.

Bivalirudin vs unfractionated heparin on stent thrombosis (within 30 days), with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The size of the data markers (squares) is approximately proportional to the statistical weight of each trial. 95%CI, 95% of confidence interval. *Data of the MATRIX trial10 not available according to clinical presentation.

A similar trend for bivalirudin was confirmed when a random-effect model was applied to the analysis (OR = 1.46; 95%CI, 0.97-2.19; P = .07; P for heterogeneity = .09).

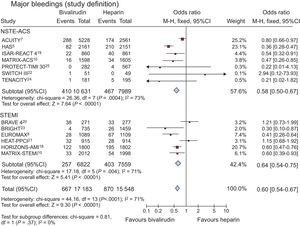

Major Bleeding Complications (per Protocol Definition)Bleedings, as per protocol definition, were reported within the first 30 days from randomization in 32 731 patients (99.9%). A major bleeding occurred in 1537 patients (4.7%), with a significant reduction of events in patients treated with bivalirudin compared with UFH (3.9%, [667 of 17 183] vs 5.6% [870 of 15 548]; OR = 0.60; 95%CI, 0.54-0.75; P < .00001; P for heterogeneity < .0001) (Figure 5). Similar results were obtained in patients with non—ST-segment elevation ACS (3.9% [410 of 10 361] vs 5.8% [467 of 7089], OR = 0.58; 95%CI, 0.50-0.67; P < .00001; P for heterogeneity = .0004). or STEMI (3.7% [257 of 6822] vs 5.3% [403 of 7559], OR = 0.64; 95%CI, 0.54-0.75; P < .00001; P for heterogeneity = .004; P for interaction = .37).

Bivalirudin vs unfractionated heparin on major bleeding complications according to protocol definition (within 30 days), with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The size of the data markers (squares) is approximately proportional to the statistical weight of each trial. 95%CI, 95% of confidence interval.

The result was confirmed when a random-effect model was applied to the meta-analysis (OR = 0.60; 95%CI, 0.46-0.77; P < .0001; P for heterogeneity < .0001).

By meta-regression analysis, no significant relationship was observed between benefits in bleeding complications with bivalirudin compared with UFH, and patient risk profiles (r = −0.09 [−0.58 to 0.39]; P = .71), whereas a positive association was found between the reduction in bleeding events with bivalirudin and the differential rate of GPIIb/IIIa use (r = −0.02[−0.033 to −0.0032]; P = .02) (Figures 6A and 6B).

Fixed-effect meta-regression analyses for the risk (odds ratio) of major bleedings between bivalirudin and unfractionated heparin according to patients’ risk profile (A) or the differential rate of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors use in the 2 groups (B). The size of the circle corresponds to the statistical weight of each study.

This is the most comprehensive meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness and safety of bivalirudin, compared with UFH in patients undergoing coronary angioplasty in the settings of ACS or STEMI. Our main finding is that bivalirudin does not reduce mortality compared with UFH but does increase stent thrombosis. However, bivalirudin is associated with a significant reduction in major bleeding complications, mainly driven by those trials administering more aggressive antithrombotic therapy with GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors in association with UFH, although this reduction did not translate into survival benefits.

The PCI is nowadays the most widely preferred strategy for the treatment of coronary artery disease,27 even in most complex coronary anatomies and especially in the setting of STEMI, where early revascularization has dramatically improved the outcome of these patients.28–30 Antithrombotic therapies have made important contributions to improving myocardial perfusion and to preventing thrombotic complications after PCI.31–33 However, progressive population aging and the increasing rate of comorbidities in patients admitted for ACS render the management of antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulation more complex, requiring a mediation between the risk of thrombosis and bleeding complications.34

Bivalirudin has emerged in the last years as an alternative anticoagulation strategy to UFH during PCI. In the first randomized trial (HAS [Hirulog Angioplasty Study])5 comparing bivalirudin with heparin in over 4000 patients undergoing PCI for a recent ACS, bivalirudin was at least as effective as UFH in preventing ischemic events and also provided a lower risk of bleeding.

Similar findings were achieved by the ACUITY trial,7 in which bivalirudin provided a significant reduction in major bleeding complications in the PCI-treated population, although it slightly increased the rate of recurrent myocardial infarction.

Analogous benefits in bleeding were reported in the HORIZONS-AMI trial,18 in which, despite a higher occurrence of stent thrombosis, bivalirudin reduced mortality in patients undergoing primary PCI, suggesting that higher-risk STEMI patients could be those that could derive the greatest benefit from bivalirudin.

Therefore, expectations of bivalirudin have been high, presenting it as the safest treatment, especially in those settings with a higher hemorrhagic risk.

However, the NAPLES-III trial,35 including elective patients undergoing PCI with a high bleeding risk score, has shown no clear benefits from the use of bivalirudin instead of UFH. Similar results have been achieved in the larger ISAR-REACT-3 trial,6 including elective patients or unstable patients with negative troponin, in which despite the higher dose of UFH (140 IU/kg), only a weak reduction in terms of TIMI (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction) major bleeding events was observed with bivalirudin.

Indeed, patients with ACS commonly have a higher risk of bleeding complications than those with stable coronary artery disease, leading to worse outcomes.36 However, the beneficial effects of bivalirudin on hemorrhagic complications have also been questioned in most recent trials including unstable patients, such as the SWITCH-III, BRAVE-4 and HEAT-PPCI studies,20–22 and in real-life registries. In particular, MacHaalany et al37 have reported no difference in net clinical adverse events or ischemic or bleeding complications with bivalirudin vs UFH, as bivalirudin reduced both ischemic and bleeding complications in patients undergoing PCI through the femoral route, but not in radial-treated patients, suggesting a potential interaction of access-site bleedings influencing the results with bivalirudin.

In addition, in a recent meta-analysis, Cavender et al38 have clearly shown that the positive effects of bivalirudin on major bleeding could be observed only when GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors were used predominantly in the UFH arm only, otherwise displaying no significant impact on bleeding. Moreover, in this meta-analysis, when compared with traditional UFH, a bivalirudin-based regimen increased the risk of myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis, confirming the safety warning that had already emerged from previous trials.

Aiming to define the safety and effectiveness of bivalirudin in PCI, and to shed light on the role of access-site and concomitant therapies, the MATRIX trial10 has recently included more than 7000 patients with ACS or STEMI undergoing a double randomization to bivalirudin or UFH and to transradial or transfemoral PCI. The study was negative for both endpoints of major adverse cardiovascular events and net adverse clinical events, with bivalirudin not emerging as statistically superior to UFH at 30 days but displaying a higher-than-expected rate of myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis. Moreover, no significant interaction of access-site was noted.

However, as the MATRIX trial included both STEMI and NSTEMI ACS patients, it remains to be determined whether any subset of patients, according to the type of ACS presentation, could most benefit from bivalirudin

In view of the relevant results of this recent large trial, the present study represents the most up-to-date meta-analysis comparing bivalirudin to UFH in patients undergoing PCI for ACS, including a prespecified subanalysis according to presentation.

Our main findings are consistent with those of previous studies showing no difference in mortality with the 2 antithrombotic regimes. As expected, bivalirudin significantly reduced the rate of major bleeding complications, but this reduction did not translate into mortality benefits. Moreover, the observed reduction in hemorrhagic complications was significantly related to the rate of GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors administered in association with UFH.

Thus, according to the present findings, and considering the potential safety concerns about the higher risk of urgent target-vessel revascularization or stent thrombosis associated with the use of bivalirudin,10,38 which have not been overcome by a longer post-PCI bivalirudin infusion, the use of the most validated and less economically-demanding strategies, such as traditional UFH-based strategies, should be advocated for patients with ACS undergoing PCI.

LimitationsThe first limitation of our study is the lack of an extended follow-up. However, bivalirudin is an intravenous drug with very fast onset of action and short half-life, thus displaying its effects only in the periprocedural period. In fact, even in the trials with longer follow-up, the differences in cardiovascular endpoints were achieved within the first month after randomization.18 One trial included mostly STEMI patients (87.7% vs 12.3% NSTEMI patients).23 As we were not able to obtain data according to the presentation, we therefore pooled this study with trials on STEMI.

Moreover, for the endpoint of stent thrombosis, the MATRIX trial10 had to be excluded due to the lack of separate data according to clinical presentation. However, the results on the overall population in this trial were in line with our present findings of an enhanced risk of ST in the bivalirudin arm, even when administered in a prolonged infusion.

Another limitation is the variable protocol of bivalirudin administration, with an extended post-PCI infusion performed in 2 trials8,10 and variations in the dosage of UFH in the control group, with 2 trials even allowing enoxaparin.8,25 However, in most of the included studies, UFH was administered at similar dosages, ranging from 60 U/kg to 75 U/kg.

CONCLUSIONSIn patients with ACS undergoing PCI, bivalirudin is not associated with a reduction in mortality compared with UFH and increases the risk of stent thrombosis. Moreover, the reduction in bleeding complications observed with bivalirudin is strictly dependent from the rate of GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor administration and does not translate into survival benefits.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- -

Bleeding complications represent the Achilles’ heel of antithrombotic therapies during PCI.

- -

The previously reported advantages in hemorrhagic risk reduction with bivalirudin during PCI have recently been questioned by potential interactions with access-site and concomitant antiplatelet strategies.

- -

In the recent MATRIX trial, bivalirudin did not provide safety benefits compared with UFH and was associated with a higher-than-expected rate of myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis.

- -

We provide the most comprehensive meta-analysis to evaluate the safety and efficacy of bivalirudin compared with UFH, including data from the most recent randomized trials in the setting of ACS.

- -

Our main finding is that bivalirudin does not provide any benefit in mortality reduction compared with UFH and increases stent thrombosis.

- -

However, bivalirudin is associated with a significant reduction in major bleeding complications, mainly driven by those trials where more aggressive antithrombotic therapy with GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors was administered only in association with UFH, and not translating into survival benefits.