The efficacy of heart failure programs has been demonstrated in clinical trials but their applicability in the real world practice setting is more controversial. This study evaluates the feasibility and efficacy of an integrated hospital-primary care program for the management of patients with heart failure in an integrated health area covering a population of 309 345.

MethodsFor the analysis, we included all patients consecutively admitted with heart failure as the principal diagnosis who had been discharged alive from all of the hospitals in Catalonia, Spain, from 2005 to 2011, the period when the program was implemented, and compared mortality and readmissions among patients exposed to the program with the rates in the patients of all the remaining integrated health areas of the Servei Català de la Salut (Catalan Health Service).

ResultsWe included 56 742 patients in the study. There were 181 204 hospital admissions and 30 712 deaths during the study period. In the adjusted analyses, when compared to the 54 659 patients from the other health areas, the 2083 patients exposed to the program had a lower risk of death (hazard ratio=0.92 [95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.97]; P=.005), a lower risk of clinically-related readmission (hazard ratio=0.71 [95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.76]; P<.001), and a lower risk of readmission for heart failure (hazard ratio=0.86 [95% confidence interval, 0.80-0.94]; P<.001). The positive impact on the morbidity and mortality rates was more marked once the program had become well established.

ConclusionsThe implementation of multidisciplinary heart failure management programs that integrate the hospital and the community is feasible and is associated with a significant reduction in patient morbidity and mortality.

Keywords

Despite treatment advances in recent decades, patients with heart failure (HF) have high rates of morbidity and mortality.1,2 Although there is evidence that adherence to clinical practice guidelines (CPG) by health care professionals during follow-up is associated with an improvement in the course of HF, the application of this evidence-based management in the real world shows a high degree of variability in daily practice.3

Randomized controlled trials have shown that organizing health care in HF management programs in accordance with the principles of the chronic care model4 improves adherence of the management strategy to the CPG and clinical outcomes.5–7

However, the real world applicability of these integrated models is unknown, largely due to their organizational complexity and to the potential biases that can occur in controlled trials evaluating these programs, which hamper extrapolation of their results to a real-world practice setting.8

To avoid the selection bias characteristic of clinical trials,9 some authors maintain that a realistic analysis of the efficacy of the disease management programs in a specific geographical location in a real world practice setting should take into account all of the individuals with the clinical condition targeted by the intervention who participate in the program, independently of the actual real world participation in the intervention: this would be the only way to obtain a realistic measure of the impact of the program on the management of the specific disease in question.10 Thus, the exposure of each participant to the geographical area where the management model has been modified would better reflect the concept of intention-to-treat, independently of whether the patient has actually been detected and registered by the program. Consequently, evaluating indicators of robust results, such as death or readmission, in all exposed patients is more likely to reflect the efficacy of an intervention in a real world practice setting than the controlled framework of a traditional clinical trial.10 This type of evaluation of experiences in pragmatic implementation has been referred to as a natural experiment.11

Thus, the objectives of the present study were to describe the organizational structure and content of an integrated hospital-primary care program for HF management, developed since 2005, in a real world practice setting in an urban integrated health area and to determine the efficacy of its implementation in reducing mortality and readmissions in high-risk patients with HF.

METHODSStudy Design and Criteria for the Selection of the Study PopulationTo evaluate the efficacy, in a real world practice setting, of a nurse-led multidisciplinary program for the management of patients with HF, integrating hospital and community resources in an urban integrated health area, we designed a population-based natural experiment that included all the patients admitted to the hospital with HF in Catalonia, Spain, between 2005 and 2011. The population-based impact on mortality and readmissions of the patients exposed to the program was evaluated, with all of the patients in the rest of the health areas of the Servei Català de la Salut (CatSalut, Catalan Health Service) constituting the control group. For the analysis, we included all consecutively admitted patients with HF who had been discharged alive in all the hospitals in Catalonia between January 2005 and June 2011, and analyzed clinically-related readmissions and survival up to September 2011. For the index admission and successive clinically-related readmissions, we considered only unplanned acute admissions of more than 24 hours’ duration. The primary outcome variable of the study was the time until the first clinically-related readmission. Secondary outcome variables were time until the first admission for HF and time to death.

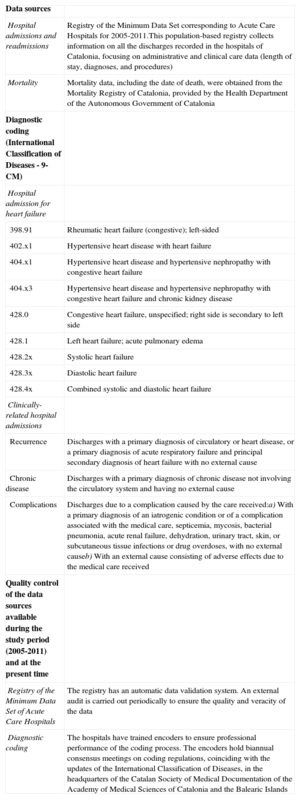

A description of the data sources and the coding criteria for the study are provided in Table 1. For both the diagnosis of HF and clinically-related admissions, we used the criteria recommended in the Chronic Condition Indicator of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.12

Data Sources, Coding Criteria for the Study, and Data Quality Control

| Data sources | |

| Hospital admissions and readmissions | Registry of the Minimum Data Set corresponding to Acute Care Hospitals for 2005-2011.This population-based registry collects information on all the discharges recorded in the hospitals of Catalonia, focusing on administrative and clinical care data (length of stay, diagnoses, and procedures) |

| Mortality | Mortality data, including the date of death, were obtained from the Mortality Registry of Catalonia, provided by the Health Department of the Autonomous Government of Catalonia |

| Diagnostic coding (International Classification of Diseases - 9-CM) | |

| Hospital admission for heart failure | |

| 398.91 | Rheumatic heart failure (congestive); left-sided |

| 402.x1 | Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure |

| 404.x1 | Hypertensive heart disease and hypertensive nephropathy with congestive heart failure |

| 404.x3 | Hypertensive heart disease and hypertensive nephropathy with congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease |

| 428.0 | Congestive heart failure, unspecified; right side is secondary to left side |

| 428.1 | Left heart failure; acute pulmonary edema |

| 428.2x | Systolic heart failure |

| 428.3x | Diastolic heart failure |

| 428.4x | Combined systolic and diastolic heart failure |

| Clinically-related hospital admissions | |

| Recurrence | Discharges with a primary diagnosis of circulatory or heart disease, or a primary diagnosis of acute respiratory failure and principal secondary diagnosis of heart failure with no external cause |

| Chronic disease | Discharges with a primary diagnosis of chronic disease not involving the circulatory system and having no external cause |

| Complications | Discharges due to a complication caused by the care received:a) With a primary diagnosis of an iatrogenic condition or of a complication associated with the medical care, septicemia, mycosis, bacterial pneumonia, acute renal failure, dehydration, urinary tract, skin, or subcutaneous tissue infections or drug overdoses, with no external causeb) With an external cause consisting of adverse effects due to the medical care received |

| Quality control of the data sources available during the study period (2005-2011) and at the present time | |

| Registry of the Minimum Data Set of Acute Care Hospitals | The registry has an automatic data validation system. An external audit is carried out periodically to ensure the quality and veracity of the data |

| Diagnostic coding | The hospitals have trained encoders to ensure professional performance of the coding process. The encoders hold biannual consensus meetings on coding regulations, coinciding with the updates of the International Classification of Diseases, in the headquarters of the Catalan Society of Medical Documentation of the Academy of Medical Sciences of Catalonia and the Balearic Islands |

Since its conception in 2005, the integrated HF management program (IHFP) is structured as a nurse-based multidisciplinary approach that arose from the amalgamation and coordination of existing health care processes and services in primary and hospital care (hospital-based multidisciplinary HF unit coordinated by the Cardiology Department) for HF patients in the Barcelona Litoral Mar Integrated Health Care Area.

In its structural and content design, an attempt was made to develop the conceptual framework provided by the chronic care model4 and to include the components proposed in the literature and CPG5–7,13: encouraging patient empowerment through promotion of self-management and self-efficacy; changing the way in which care is provided from the conventional form to a more proactive approach, with interventions based on new nursing roles (specialized in HF and as case managers), cardiologists specialized in HF, and other multidisciplinary contributions; flexible health care services that provide open access to patients (for example, day hospitals for those with HF); new technologies, such as telemedicine, for communication among patients, caregivers and health care professionals; promotion of the use of tools and strategies to support decision-making by specialized nurses, community nurses, and family physicians (decision algorithms based on the CPG); promoting the use of electronic information systems to improve communication among health care professionals (integration of the electronic health record among caregivers) to support decision-making by primary care professionals and to evaluate outcomes. The health care context, organizational features, and characteristics of the development of the IHFP are shown in Table 2.

Description of the Organizational Context, Development, Health Care Resources, and Contents of the Integrated Heart Failure Management Program of the Barcelona Litoral Mar Integrated Health Care Area

| Context: health care organization | |

| CatSalut | Divided into 44 territorial units grouped into 6 health care regions, covers 98% of the 7 539 618 residents of Catalonia. In the city of Barcelona, the territorial units are referred to as Integrated Health Areas. |

| Litoral Mar IHA of Barcelona | Area of multilevel and multiprovider health care coordination (districts ofCiutat Vella and Sant Martí) for its population of 309 345 |

| Litoral Mar IHFP | Health care network for patients with HF constructed in the Litoral Mar IHA in Barcelona. The network integrates health care institutions that include Hospital del Mar (Parc de Salut Mar), the 11 PC centers (PC of the Litoral PC Service of the ICS), the 2 PC centers administered by the Instituto de Prestación Médica del Personal Municipal (Institute of Medical Assistance for Municipal Personnel [PAMEM]), and other providers |

| Specific measures taken in the development of the program | |

| Creation of the Working Group | |

| Objectives | Agreement on the process of managing HF patients in the IHA following a common HCP |

| Executive coordination | A hospital-based cardiologist specialized in HF and a PC-based physician specialized in family and commonity medicine, who report to their respective management teams and to that of the AIS |

| Members of the hospital HF unit | Cardiologists and nurses specialized in HF, pharmacists, physical therapists, a rehabilitation physician, a geriatric clinical nurse and geriatrician, neuropsychologists, a clinical psychologist, a social worker, a nutritionist, a diabetologist, an emergency physician, and a physician and a nurse from the hospital palliative care team |

| PC members | Family physicians and nurses (ICS, PAMEM, MUTUAM), case managers and professionals from the primary care emergency centers and from the home palliative care teams |

| Lines of work developed and actions undertaken | |

| Portfolio of services provided jointly | Integration in a single joint services portfolio of all the resources useful to the HF management process, whether hospital-based or provided by PC centers or other community institutions |

| HCP primary care leader | A physician and a nurse in each PC center with the tasks of guaranteeing the improvement and implementation of the HCP, contributing to the continuing education of the team, and coordinating patient care between the HF unit and PC |

| Educational process | Agreement on the material needed to encourage self-care among patients, caregivers and relatives |

| Communication among professionals | Definition of the methods and channels of communication among levels of care |

| Definition of the norms for the contents of reports concerning transitions involving patients | |

| Request for prioritization in the process of integrating electronic health records from PC and the hospital | |

| Health care pathway | The design of clinical practice guidelines, agreed by consensus, for HF management |

| Definition of patient flow within the IHFP and of the methods of identification, labeling, and inclusion in the HCP | |

| Definition of the criteria and the channels through which patients make the transition from one care setting to another | |

| Definition of the transitions along the HCP throughout the patient's course | |

| Clinical pathway for the structured follow-up of patients eligible for home care | |

| Clinical pathway for the structured follow-up of patients being followed by means of telemedicine | |

| Protocol for ambulatory follow-up in the HF day hospital | |

| Joint planning process for hospital discharge and the transition from hospital to home | |

| Training | Training workshops for family physicians, nurse case managers, and PC nurses |

| Rotations for the training of HCP PC leaders in the hospital-based HF unit | |

| Update sessions during the periodical meetings of the working group (every 6 months) | |

| Dynamics of the process of creating the IHFP | Process of progressive implementation. Participation of the persons responsible for the health care policies of the IHA, patients, caregivers, PC cardiologists, those responsible for hospital-PC coordination, and their respective management teams |

| Institutions, resources, and health care processes involved in the program | |

| Hospital | Preparing the HF day-hospital for the structured follow-up and ambulatory management of decompensation (open access) |

| Systematic process for in-hospital intervention and discharge planning (transitions from hospital to PC) | |

| Establishment of structured follow-up processes for the early detection of decompensation, reevaluation of the diagnosis, and optimization of therapy (HF cardiologists and nurses) with traditional models (day-hospital) and virtual models (telemedicine) | |

| Process of evaluation and follow-up of frailty (geriatricians and neuropsychologists) | |

| Intervention of pharmacists (self-management, drug-related problems, and coordination with community pharmacies) | |

| Specific process for the indication and monitoring of candidates for implantable devices or advanced HF solutions (Heart Team) | |

| Joint follow-up of patients with implantable devices in a single outpatient clinic (implant specialists, HF specialist, and imaging services) | |

| Rehabilitation and physical training program for HF patients | |

| Development of a web page specifically designed for the program for use by patients and professionals of the area | |

| Development of educational materials for patients and caregivers | |

| PC | Establishment of a structured follow-up process for the early detection of decompensation and optimization of therapy in the frail patient by means of a specific clinical pathway based on home intervention (case manager) |

| Protocol for the detection and inclusion in the HCP of individuals with HF detected out of hospital in the PC setting | |

| Conventional educational groups and an expert primary care patient program (ICS)* | |

| ICS electronic clinical practice guidelines for HF* | |

| Center for telephone follow-up of chronic diseases (ICS) for standardized education of HF patients* | |

| Training workshops for caregivers | |

| PC physical activity groups* | |

| Joint actions on the part of the hospital and PC | Joint design of the HCP for HF management in the IHA |

| Integration of emergency care (PC and hospital) into the HCP process | |

| Key strategic actions | Process based on local clinical leaders and the health care pact represented by the HCP |

| Integral assessment of patients, their environment, and support systems and the design of specific clinical pathways, depending on risk and psychosocial factors. This process has allowed patients to be included from the entire spectrum of comorbidities and ventricular function | |

| Management process focusing on specialized hospital nursing (HF nurses) and PC nursing (case managers) | |

| Discharge planning process with weekly face-to-face encounters between HF nursing staff and PC case managers | |

| Continuing education plan (periodical sessions and rotations) | |

| Dissemination of the model to other health areas (ITERA program) | |

| Involvement of the respective administrations and the CatSalut | |

| Prioritization of the process of integrating electronic health records at all levels | |

| Follow-up of the results by means of the follow-up modules of quality indicators of the CatSalut |

CatSalut, Catalan Health Service; HCP, health care pathway; HF, heart failure; ICS, Institut Català de la Salut; IHA, integrated health area; IHFP, integrated heart failure program; PC, primary care; TRU, territorial reference unit.

*Services and resources available in other TRU.

To measure the quality, complexity, and intensity of our program, we calculated the recently proposed indices for their evaluation in the field of HF programs using the Heart Failure Intervention Score,14 which assesses the quality of an intervention according to the number of evidence-based interventions implemented, and the Heart Failure Disease Management Scoring Instrument,15 which rates the quality of a program using 10 items that describe its design. In both instruments, the higher the score, the higher the quality.

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are expressed as the mean (standard deviation), and categorical variables as the number (%).Comparisons between categorical variables were carried out with the chi-square test and comparisons of continuous variables, with Student's t test. The primary outcome variable was the time to the first adverse clinical event. A simple (univariate) Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the clinical variables associated with the outcome variables. Subsequently, using the variables associated with a significant risk of experiencing the clinical events evaluated here, which included a wide range of comorbidities, we constructed 3 multivariate models by calculating the Cox proportional hazards, using a stepwise backward elimination method. Three different models were generated to determine the clinical factors associated with a clinically-related risk of readmission, readmission for HF, and mortality. Using these models, we generated the resulting adjusted survival curves. These same models were repeated separately according to the period of implementation of the IHFP (initial period or the period of full establishment or consolidation). For this analysis, the adjusted probabilities of experiencing any of the clinical events studied here are graphically represented, according to the period, on the basis of Cox proportional hazards models. Finally, to perform an integrated analysis of the impact of the intervention on mortality and clinically-related readmission, we analyzed the probability of experiencing any of these adverse events during the follow-up period.16 A P value less than .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS software package (version 18).

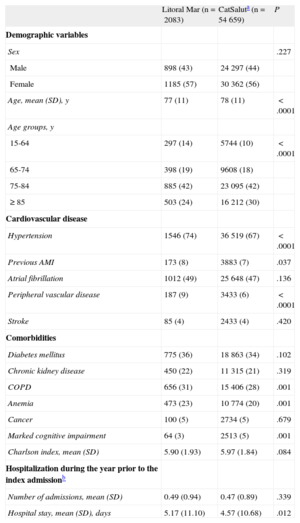

RESULTSAmong the population of 56 742 patients included in this study, there were 181 204 hospital admissions and 30 712 deaths. The 2083 patients exposed to the IHFP were younger (77 years vs 78 years; P<.05), had a higher prevalence of previous acute myocardial infarction (8% vs 7%; P<.05), and a lower prevalence of dementia, but had a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as COPD (31% vs 28%; P<.05) and anemia (23% vs 20%; P<.05) than the 54 659 patients in the other health areas (Table 3). There were no significant differences in other variables such as the number of hospital admissions in the year prior to inclusion in the study, or the presence of diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, among others. In the crude analyses, following the index admission, the patients exposed to the IHFP had lower averages of clinically-related readmissions (2.04 [2.7] vs 2.20 [2.9]; P=.016) and readmissions for HF (0.57 [1.2] vs 0.65 [1.3]; P=.007) and lower rates of clinically-related readmissions (39% vs 50%; P<.001), readmissions for HF (31.3% vs 33.8%; P=.008), and mortality (818 patients [50%] vs 27 125 patients [54%]; P<.0001) than the patients followed up in the other health areas of the CatSalut.

Descriptive Analysis of the Study Population. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics According to Analysis Group

| Litoral Mar (n=2083) | CatSaluta (n=54 659) | P | |

| Demographic variables | |||

| Sex | .227 | ||

| Male | 898 (43) | 24 297 (44) | |

| Female | 1185 (57) | 30 362 (56) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 77 (11) | 78 (11) | <.0001 |

| Age groups, y | |||

| 15-64 | 297 (14) | 5744 (10) | <.0001 |

| 65-74 | 398 (19) | 9608 (18) | |

| 75-84 | 885 (42) | 23 095 (42) | |

| ≥ 85 | 503 (24) | 16 212 (30) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

| Hypertension | 1546 (74) | 36 519 (67) | <.0001 |

| Previous AMI | 173 (8) | 3883 (7) | .037 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1012 (49) | 25 648 (47) | .136 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 187 (9) | 3433 (6) | <.0001 |

| Stroke | 85 (4) | 2433 (4) | .420 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 775 (36) | 18 863 (34) | .102 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 450 (22) | 11 315 (21) | .319 |

| COPD | 656 (31) | 15 406 (28) | .001 |

| Anemia | 473 (23) | 10 774 (20) | .001 |

| Cancer | 100 (5) | 2734 (5) | .679 |

| Marked cognitive impairment | 64 (3) | 2513 (5) | .001 |

| Charlson index, mean (SD) | 5.90 (1.93) | 5.97 (1.84) | .084 |

| Hospitalization during the year prior to the index admissionb | |||

| Number of admissions, mean (SD) | 0.49 (0.94) | 0.47 (0.89) | .339 |

| Hospital stay, mean (SD), days | 5.17 (11.10) | 4.57 (10.68) | .012 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CatSalut, Catalan Health Service; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SD, standard deviation.

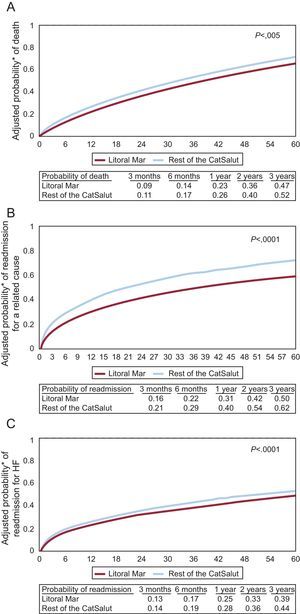

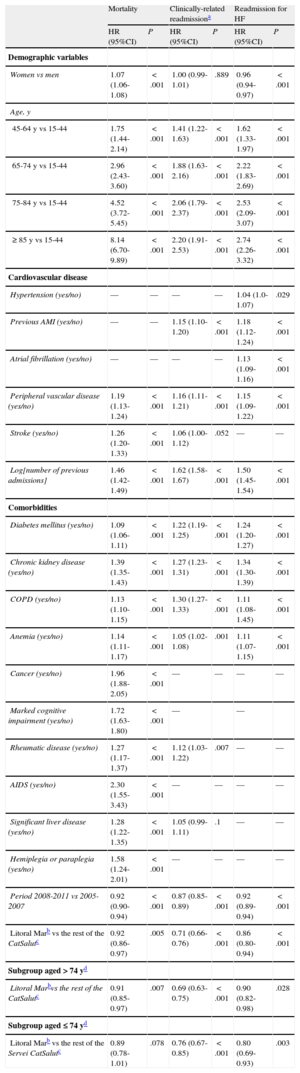

In the multivariate Cox analysis adjusted for covariates associated with the clinical events studied (including age and sex), with an additional analysis stratified by age, the patients followed up in the IHFP (Table 4, Figure 1A-C) had a lower risk of death (hazard ratio [HR]=0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.86-0.97; P=0.005), of clinically-related readmission (HR=0.71; 95%CI, 0.66-0.76; P<0.001), and of readmission for HF (HR=0.86; 95%CI, 0.80-0.94; P<0.001).

Multivariate Regression Analysis Using a Cox Proportional Hazards Model to Determine the Predictive Factors for Death, Clinically-related Readmission,a and Readmission for Heart Failure between 2005 and 2011 in the Cohort of 56 742 Patients Studied

| Mortality | Clinically-related readmissiona | Readmission for HF | ||||

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| Demographic variables | ||||||

| Women vs men | 1.07 (1.06-1.08) | <.001 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | .889 | 0.96 (0.94-0.97) | <.001 |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 45-64 y vs 15-44 | 1.75 (1.44-2.14) | <.001 | 1.41 (1.22-1.63) | <.001 | 1.62 (1.33-1.97) | <.001 |

| 65-74 y vs 15-44 | 2.96 (2.43-3.60) | <.001 | 1.88 (1.63-2.16) | <.001 | 2.22 (1.83-2.69) | <.001 |

| 75-84 y vs 15-44 | 4.52 (3.72-5.45) | <.001 | 2.06 (1.79-2.37) | <.001 | 2.53 (2.09-3.07) | <.001 |

| ≥ 85 y vs 15-44 | 8.14 (6.70-9.89) | <.001 | 2.20 (1.91-2.53) | <.001 | 2.74 (2.26-3.32) | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Hypertension (yes/no) | — | — | — | — | 1.04 (1.0-1.07) | .029 |

| Previous AMI (yes/no) | — | — | 1.15 (1.10-1.20) | <.001 | 1.18 (1.12-1.24) | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation (yes/no) | — | — | — | — | 1.13 (1.09-1.16) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (yes/no) | 1.19 (1.13-1.24) | <.001 | 1.16 (1.11-1.21) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.09-1.22) | <.001 |

| Stroke (yes/no) | 1.26 (1.20-1.33) | <.001 | 1.06 (1.00-1.12) | .052 | — | — |

| Log[number of previous admissions] | 1.46 (1.42-1.49) | <.001 | 1.62 (1.58-1.67) | <.001 | 1.50 (1.45-1.54) | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus (yes/no) | 1.09 (1.06-1.11) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.19-1.25) | <.001 | 1.24 (1.20-1.27) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease (yes/no) | 1.39 (1.35-1.43) | <.001 | 1.27 (1.23-1.31) | <.001 | 1.34 (1.30-1.39) | <.001 |

| COPD (yes/no) | 1.13 (1.10-1.15) | <.001 | 1.30 (1.27-1.33) | <.001 | 1.11 (1.08-1.45) | <.001 |

| Anemia (yes/no) | 1.14 (1.11-1.17) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.02-1.08) | .001 | 1.11 (1.07-1.15) | <.001 |

| Cancer (yes/no) | 1.96 (1.88-2.05) | <.001 | — | — | — | — |

| Marked cognitive impairment (yes/no) | 1.72 (1.63-1.80) | <.001 | — | — | ||

| Rheumatic disease (yes/no) | 1.27 (1.17-1.37) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.03-1.22) | .007 | — | — |

| AIDS (yes/no) | 2.30 (1.55-3.43) | <.001 | — | — | — | — |

| Significant liver disease (yes/no) | 1.28 (1.22-1.35) | <.001 | 1.05 (0.99-1.11) | .1 | — | — |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia (yes/no) | 1.58 (1.24-2.01) | <.001 | — | — | — | — |

| Period 2008-2011 vs 2005-2007 | 0.92 (0.90-0.94) | <.001 | 0.87 (0.85-0.89) | <.001 | 0.92 (0.89-0.94) | <.001 |

| Litoral Marb vs the rest of the CatSalutc | 0.92 (0.86-0.97) | .005 | 0.71 (0.66-0.76) | <.001 | 0.86 (0.80-0.94) | <.001 |

| Subgroup aged>74 yd | ||||||

| Litoral Marbvs the rest of the CatSalutc | 0.91 (0.85-0.97) | .007 | 0.69 (0.63-0.75) | <.001 | 0.90 (0.82-0.98) | .028 |

| Subgroup aged ≤ 74 yd | ||||||

| Litoral Marb vs the rest of the Servei CatSalutc | 0.89 (0.78-1.01) | .078 | 0.76 (0.67-0.85) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.69-0.93) | .003 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR, hazards ratio.

Survival curves estimated on the basis of multivariate Cox models for adjusted probability of death (A), clinically-related readmission (B), and readmission for heart failure (C) during the study period (2005-2011). CatSalut, Catalan Health Service; HF, heart failure.

*Probability adjusted for the variables associated with the outcome variable in the corresponding multivariate Cox proportional hazards models (Table 4).

Interestingly, the period factor (initial or consolidation) was independently associated with an adjusted risk of mortality, clinically-related readmission, and readmission for HF (Table 4): in all the patients analyzed, the adjusted relative risk of the occurrence of the events studied here was lower in the second period (2008-2011) than in the first (2005 to 2007).

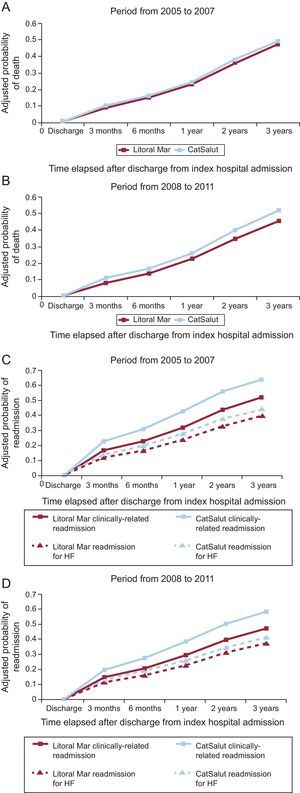

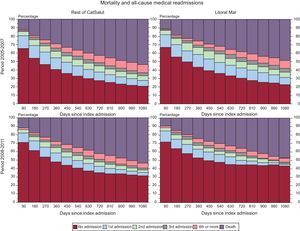

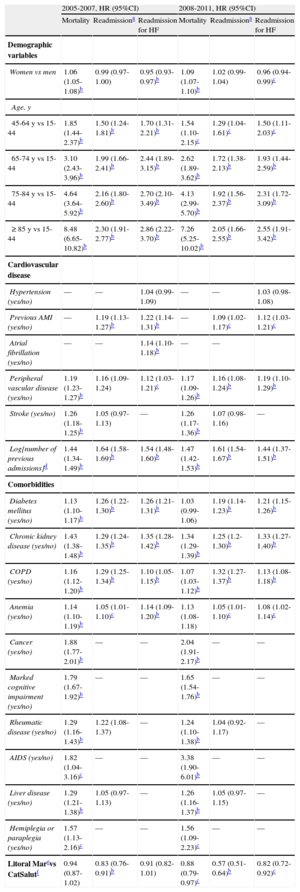

In a separate analysis of the initial period of the IHFP (2005-2007) and the consolidation period (2008-2011) (Table 5, Figure 2A-C), follow-up in the IHFP had a neutral effect on the adjusted risk of mortality (HR=0.94; 95%CI, 0.87-1.02) and readmission for HF (HR=0.91; 95%CI, 0.82-1.01) in the initial period, whereas in the consolidation period, the reductions in the adjusted risk of mortality (HR=0.88; 95%CI, 0.79-0.97) and readmission for HF (HR=0.82; 95%CI, 0.72-0.92) were significant (P<0.05 for both). The reduction in the adjusted risk of clinically-related readmission was significant in the initial period (HR=0.83; 95%CI, 0.76-0.91) and the consolidation period (HR=0.57; 95%CI, 0.51-0.64) (P<.001 for both). The probability of any of the adverse events studied occurring over time is shown in Figure 3. As can be seen, the outcomes for the initial period were worse in both groups: after 3 years of follow-up, only 20% of the study patients had had no adverse events, although the mortality rate in those followed-up in the IHFP was 5% lower. In the consolidation period, the differences were more evident: after 3 years of follow-up, 43% of the patients followed up in the IHFP had had no adverse events, whereas this percentage fell to 32% in the rest of the population, and the mortality rate remained similar to that observed in the earlier period.

Multivariate Regression Analysis Using a Cox Proportional Hazards Model to Determine the Factors Predictive of Death, Clinically-related Readmission,a and Readmission for Heart Failure in the Cohort of 56 742 Patients Studied Either in the Initial Period (2005-2007) or in the Period in which the Program Became Consolidated (2008-2011)

| 2005-2007, HR (95%CI) | 2008-2011, HR (95%CI) | |||||

| Mortality | Readmissiona | Readmission for HF | Mortality | Readmissiona | Readmission for HF | |

| Demographic variables | ||||||

| Women vs men | 1.06 (1.05-1.08)b | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | 0.95 (0.93-0.97)b | 1.09 (1.07-1.10)b | 1.02 (0.99-1.04) | 0.96 (0.94-0.99)c |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 45-64 y vs 15-44 | 1.85 (1.44-2.37)b | 1.50 (1.24-1.81)b | 1.70 (1.31-2.21)b | 1.54 (1.10-2.15)c | 1.29 (1.04-1.61)c | 1.50 (1.11-2.03)c |

| 65-74 y vs 15-44 | 3.10 (2.43-3.96)b | 1.99 (1.66-2.41)b | 2.44 (1.89-3.15)b | 2.62 (1.89-3.62)b | 1.72 (1.38-2.13)b | 1.93 (1.44-2.59)b |

| 75-84 y vs 15-44 | 4.64 (3.64-5.92)b | 2.16 (1.80-2.60)b | 2.70 (2.10-3.49)b | 4.13 (2.99-5.70)b | 1.92 (1.56-2.37)b | 2.31 (1.72-3.09)b |

| ≥ 85 y vs 15-44 | 8.48 (6.65-10.82)b | 2.30 (1.91-2.77)b | 2.86 (2.22-3.70)b | 7.26 (5.25-10.02)b | 2.05 (1.66-2.55)b | 2.55 (1.91-3.42)b |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Hypertension (yes/no) | — | — | 1.04 (0.99-1.09) | — | — | 1.03 (0.98-1.08) |

| Previous AMI (yes/no) | — | 1.19 (1.13-1.27)b | 1.22 (1.14-1.31)b | — | 1.09 (1.02-1.17)c | 1.12 (1.03-1.21)c |

| Atrial fibrillation (yes/no) | — | — | 1.14 (1.10-1.18)b | — | — | |

| Peripheral vascular disease (yes/no) | 1.19 (1.23-1.27)b | 1.16 (1.09-1.24) | 1.12 (1.03-1.21)c | 1.17 (1.09-1.26)b | 1.16 (1.08-1.24)b | 1.19 (1.10-1.29)b |

| Stroke (yes/no) | 1.26 (1.18-1.25)b | 1.05 (0.97-1.13) | — | 1.26 (1.17-1.36)b | 1.07 (0.98-1.16) | — |

| Log[number of previous admissions]d | 1.44 (1.34-1.49)b | 1.64 (1.58-1.69)b | 1.54 (1.48-1.60)b | 1.47 (1.42-1.53)b | 1.61 (1.54-1.67)b | 1.44 (1.37-1.51)b |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus (yes/no) | 1.13 (1.10-1.17)b | 1.26 (1.22-1.30)b | 1.26 (1.21-1.31)b | 1.03 (0.99-1.06) | 1.19 (1.14-1.23)b | 1.21 (1.15-1.26)b |

| Chronic kidney disease (yes/no) | 1.43 (1.38-1.48)b | 1.29 (1.24-1.35)b | 1.35 (1.28-1.42)b | 1.34 (1.29-1.39)b | 1.25 (1.2-1.30)b | 1.33 (1.27-1.40)b |

| COPD (yes/no) | 1.16 (1.12-1.20)b | 1.29 (1.25-1.34)b | 1.10 (1.05-1.15)b | 1.07 (1.03-1.12)b | 1.32 (1.27-1.37)b | 1.13 (1.08-1.18)b |

| Anemia (yes/no) | 1.14 (1.10-1.19)b | 1.05 (1.01-1.10)c | 1.14 (1.09-1.20)b | 1.13 (1.08-1.18) | 1.05 (1.01-1.10)c | 1.08 (1.02-1.14)c |

| Cancer (yes/no) | 1.88 (1.77-2.01)b | — | — | 2.04 (1.91-2.17)b | — | — |

| Marked cognitive impairment (yes/no) | 1.79 (1.67-1.92)b | — | — | 1.65 (1.54-1.76)b | — | — |

| Rheumatic disease (yes/no) | 1.29 (1.16-1.43)b | 1.22 (1.08-1.37) | — | 1.24 (1.10-1.38)b | 1.04 (0.92-1.17) | — |

| AIDS (yes/no) | 1.82 (1.04-3.16)c | — | — | 3.38 (1.90-6.01)b | — | — |

| Liver disease (yes/no) | 1.29 (1.21-1.38)b | 1.05 (0.97-1.13) | — | 1.26 (1.16-1.37)b | 1.05 (0.97-1.15) | — |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia (yes/no) | 1.57 (1.13-2.16)c | — | — | 1.56 (1.09-2.23)c | — | — |

| Litoral Marevs CatSalutf | 0.94 (0.87-1.02) | 0.83 (0.76-0.91)b | 0.91 (0.82-1.01) | 0.88 (0.79-0.97)c | 0.57 (0.51-0.64)b | 0.82 (0.72-0.92)c |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CatSalut, Catalan Health Service; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR, hazard ratio.

A and B: adjusted probability of death during the periods from 2005 to 2007 (P=.123) and from 2008 to 2011 (P=.008). C and D: adjusted probability of readmission during the periods from 2005 to 2007 (P<.001 for clinically-related readmission; P=.085 for readmission for HF) and from 2008 to 2011 (P<.001 for clinically-related readmission; P=.001 for readmission for HF). The P values correspond to the comparison between the Barcelona Litoral Mar Integrated Health Care Area and the other health areas of the CatSalut. Adjustment was made for the variables associated with the outcome variable in the corresponding multivariate Cox proportional hazards models (Table 5). CatSalut, Catalan Health Service; HF, heart failure.

Graph based on an approach proposed by Selwood that analyzes the clinical events experienced by the patients (mortality and morbidity) in an integrated manner according to the study groups (Litoral Mar vs the rest of the institutions of the CatSalut) and according to the period analyzed. CatSalut, Catalan Health Service.

To measure the quality of our program, we calculated the indices recently proposed for evaluation of the quality of HF programs. In the Heart Failure Intervention Score,14 our program obtained 197 points (out of a maximum of 198). In the Heart Failure Disease Management Scoring Instrument (HF-DMSI),15 our program obtained the highest possible score in all 10 items.

DISCUSSIONIn this population-based, retrospective study, the implementation of HF management programs that integrate hospital and community resources was feasible and was associated with a greater efficacy of robust outcome indicators that are relevant to the health care system and patients. These findings are in line with those reported in a number of randomized controlled clinical trials showing that the organization of the interdisciplinary HF management process is the approach that offers the best clinical outcomes and should be the standard of care in these patients.5–7,13

In our study, follow-up in the IHFP, compared with that of the remaining health areas, resulted in a relative reduction of the risk of death, clinically-related readmission, and readmission for HF of 8%, 29%, and 14%, respectively. Importantly, from 2008 to 2011, when the organizational structure was becoming more consolidated, we observed relative reductions of the risk of death, clinically-related readmission, and readmission for HF of 12%, 43%, and 18%, respectively.

The magnitude of the benefit shown in this study was similar to that reported in previous meta-analyses of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of HF programs, in which the reductions in the risk of death and of readmission were around 20% in both cases.6,7 This finding is especially important because it demonstrates that the results obtained in the clinical trial setting can be transferred to a real world practice setting.

The period from 2008 to 2011 was associated with an improvement in the indicators not only in the patients in the IHFP, but also in those covered by the other health areas. This general improvement could be related to a number of factors, such as greater awareness of the importance of HF in both specialized and primary care, the introduction of electronic CPG in primary care, the creation of new HF units, and the efforts made by the different health care providers to improve the HF management process applied in Catalonia that materialized in 2006 as an integrated care plan for HF (Pla d’Atenció Integral a la Insuficiència Cardiaca a Catalunya) within the framework of a strategic plan for diseases of the circulatory system.17,18 Nevertheless, the improvement in the indicators was more marked in the patients in the IHFP, highlighting the fact that not all organizational models are equally effective.6–8,19–21

Both the organization and contents of heart failure programs can vary. Therefore, there is a need for tools that would allow evaluation of the quality of these programs and facilitate their comparison.14,15 The organizational models for HF management that have been most successful in improving outcomes are those focussing on the patients at highest risk, that include multidisciplinary interventions, and achieve integration between hospital-based and primary care HF units, with an important role for specialized and community nursing teams in the process of patient management and coordination.6,7,13,14,22,23 These organizational models are rated as a class I recommendation with level A evidence in the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for HF management.5,13 The organizational and intervention model of the IHFP of the Barcelona Litoral Mar Integrated Health Care Area comprises all the components recommended in the CPG and in the chronic disease model (Table 2), and is proof that, with the resources available, organizations of this type are feasible in the majority of the health areas in our health care setting.4,5,7,13 Along these lines, the scores received in the evaluation of our program using recently published indices for the evaluation of the organization of HF management processes are compatible with a high standard of quality of care.14,15

The major difference between the present study and previously reported clinical trials is that out study was designed as a natural experiment.11 In this pragmatic evaluation, we analyzed all the patients attended by the integrated health area where the changes had been made, regardless of whether or not each particular patient had actually been selected to undergo the process, and compared their course with that of a control group consisting of the remainder of the patients of the CatSalut. This enabled us to minimize the selection bias characteristic of clinical trials, in which the profile of included patients is often very different from that of patients observed in the real world and more pragmatically reflects the efficacy of the intervention.9,10,24,25 A similar methodology was used in recent publications20,21 analyzing the effect of comparable interventions in large populations of patients with HF.

An important conclusion that can be drawn from the data in this study is that, despite advances in the management of HF, outcome remains poor. In our sample of 56 742 patients, there were 181 204 hospital admissions and 30 712 deaths during the study period. These high rates contrast with those observed in recent clinical trials,26–28 registries,29 and even population-based studies30,31 involving patients from our geographical region that analyzed mortality and hospital admissions in HF patients detected in the community, although they are similar to those found in population-based registries based on hospital admissions.32 This difference in clinical events compared with those in other studies33 could be explained by the high rate of comorbidity in the patients included in this analysis and by their inclusion in the study after admission for HF for HF (index admission).33

LimitationsThe major limitation of this natural experiment is its retrospective design.11 The ability of this design to establish causality is limited, although the data obtained reveal an association between the transformation carried out in our area and the improvement in the clinical outcomes compared with those in the comparator. In this respect, the retrospective design entails an absence of control over allocation of the intervention and an absence of information on the treatment received by the patients and their ventricular function. Nevertheless, the inclusion of all the patients admitted to hospital for HF in Catalonia during the study period enabled us to avoid the selection bias characteristic of clinical trials9 and facilitated dissemination of the results.10 Another limitation was our inability to determine the components of the design that were most effective and, thus, the results of the IHFP should be analyzed as a whole. Moreover, patient inclusion was based on diagnosis of HF at the time of discharge. Although this may entail a risk of diagnostic inaccuracy, importantly, the methodology for diagnosis and causal attribution used in this analysis was agreed by consensus among the encoders of the different hospitals, and is validated and audited periodically. These aspects of control and quality of the data are fundamental, since this information is used for analysis of demand and funding of our health care system and for decision-making on health policy in our general population.12 The main objective of this study was to determine the effect of the intervention on clinically-related admissions. Although the specificity might seem low and, as an indicator, there is probably room for improvement, this approximation only excludes hospital admissions due to unrelated causes, takes into account the multimorbidity encountered in the HF population, and better reflects an intervention that, although focused on HF, was designed for the integrated care of patients with acute exacerbation of a chronic disease. These considerations and the application of the criteria for clinically-related readmission throughout the entire study and in the same way in all of the areas confer validity on the results reported here.

CONCLUSIONSThe benefits of multidisciplinary HF management programs that integrate hospital and community can be extrapolated to daily practice. Although complex, their implementation is feasible with the available resources and is associated with a significant reduction in mortality and readmissions for HF and other clinically-related causes. The benefits of the implementation of these programs are apparent in the short term and improve once the program has become consolidated. We need to promote the creation of similar processes in other geographical areas, as well as the continuous evaluation of their efficacy in each specific setting. To achieve these milestones, cooperation between the administration and professionals is essential to steer our health care system toward the care of chronic diseases.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

M. Guerrero, M. Grillo, A. Ramírez, R. Crespo, E. Calero, P. Furió, J. López, E. Carrera, M. Rodríguez, J.J. Zamora, C. Enjuanes, S. Ruiz, M. Rizzo, A. Linas, P. Ruiz, L. Ollé, C. Ivern, B. García-Bascuñana, M. Corral, P. Cabero, C. Soler, N. Rodríguez, M. Forné, C. Crespo, E. Salas, S. Luque, J. Flores, A. Aguirre, J. Peña, R.M. Manero, F. Escalada, D. Rodríguez, A. Ballester, E. Marco, O. Vázquez, M. Garreta, J. Gutiérrez, M. Claret, M. Gasulla, J. Planas, G. Colomer, I. Coll, M. Luna, M. Roig, A. Casado, Q. Guitart, L. Pifarré, R. Ruiz, N. Martí, A. Torres, P. Escobar, J. Casas, R. Aragonés, H. Cebrián, J.M. Rodríguez-Galipienzo, R.M. Solé, M. Ballester, C. Lladosa, V. Golobart, L. Viñas, T. Espejo, A. Guarner, C. Medrano, J. Bayó, E. Gil, J.M. Vigatà, S. Martí, Y. Barroso, J.M. Casacuberta, S. García, C. Piedra, C. Casanovas, C. Royo, V. Salido, F. Ramos, E. Esquerra, B. Sena, A. Bassa, M. Cabañas, M. López, L. Recasens, R. Serrat, C. García, O. Meroño, N. Ribas, M. Ble, V. Bazán, J. Martí, J. Morales, M. Gómez, A. Sainz, N. Pujolar, E. Maull, O. Pané, F. Bory, B. Enfedaque, R. Ruiz, M. Boixadera, C. Minguell, C. Duran, and J. Estany.