Opioids and benzodiazepines are the sedative and analgesic drugs of choice for pediatric patients in cardiac intensive care units. Long-term use of these drugs is associated with the development of withdrawal syndrome. In pediatric patients this is difficult to diagnose due to a wide range of nonspecific symptoms and the scarcity of validated diagnostic scales. In pediatrics, incidence of withdrawal syndrome is 35% to 57%; the greater the accumulated dose and length of treatment, the more frequently it occurs.1 Accumulated doses of phentanyl of >1.6 mg/kg or >5 days of infusions are associated with developing withdrawal syndrome; with doses of >2.5 mg/kg or >9 days of infusions, incidence of up to 100% has been described.2

In pediatric heart transplantation, due to the scarcity of donors the waiting list times increase, extracorporeal circulatory support becomes necessary, cardiac intensive care units stay lengthens, and the probability of developing withdrawal syndrome increases.3 Dexmedetomidine, an α2-adrenergic agonist, is a sedative and analgesic with possibly beneficial effects in controlling withdrawal syndrome.4 As both a sedative and analgesic agent that does not cause depression of the respiratory center, it has gained widespread acceptance for use in pediatric cardiac intensive care units in the USA. Numerous publications report its efficacy and safety.5 However, evidence of its use in preventing withdrawal syndrome, particularly in the cardiac posttransplantation period, is scarce.4

We describe our experience with dexmedetomidine in managing withdrawal syndrome and supporting opioid discontinuation in 2 pediatric heart transplant recipients.

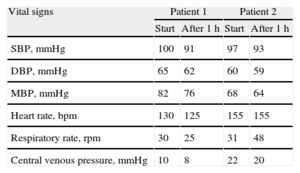

Case 1. Infant aged 11 months transplanted for dilated cardiomyopathy due to myocarditis, who had required 7 days of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support and ventricular assist device implantation during the 20 days preceding transplantation. Sedation and analgesia were administered in a continuous infusion of opioids, benzodiazepine, and propofol. The patient experienced withdrawal syndrome and morphine dosage could not be reduced despite having started the standard management protocol. The accumulated opioid dose was 1.39 mg/kg in 33 days. We decided to start treatment with dexmedetomidine in continuous infusion with an initial dose of 0.75 μg/kg/h and maximum of 1 μg/kg/h, enabling us to rapidly reduce the opioid without withdrawal syndrome reappearing (Figure A). The patient remained hemodynamically stable after starting the dexmedetomidine regimen and no side effects of its use were observed (Table).

Clinical Course of Hemodynamic Parameters After Initiating a Dexmedetomidine Regimen

| Vital signs | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | ||

| Start | After 1h | Start | After 1h | |

| SBP, mmHg | 100 | 91 | 97 | 93 |

| DBP, mmHg | 65 | 62 | 60 | 59 |

| MBP, mmHg | 82 | 76 | 68 | 64 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 130 | 125 | 155 | 155 |

| Respiratory rate, rpm | 30 | 25 | 31 | 48 |

| Central venous pressure, mmHg | 10 | 8 | 22 | 20 |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MBP, mean blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Case 2. A 5-year-old boy was transplanted for noncompaction cardiomyopathy; he had previously been hospitalized for 11 months with ventricular assist device, requiring 5 days postoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Sedation and analgesia were administered in a continuous infusion of opioids, benzodiazepine, and propofol. He experienced withdrawal syndrome and morphine dosage could not be reduced. The accumulated opioid dose was 1.21 mg/kg in 16 days. We decided to start a dexmedetomidine regimen with continuous infusion at 1 μg/kg/h. After initiating treatment, the morphine dosage was tapered over 6 days without withdrawal syndrome reappearing. At that point, humoral rejection was diagnosed and the patient needed a change of sedative and analgesic to undergo diagnostic tests and venous access cannulation. The dexmedetomidine regimen was suspended for 4 days; morphine was increased and propofol added. Later, dexmedetomidine administration was restarted, propofol suspended, and morphine tapered with cessation at 7 days (Figure B). The patient remained hemodynamically stable and no dexmedetomidine-derived side effects were observed (Table).

In both patients, the use of dexmedetomidine to prevent opioid withdrawal syndrome in the cardiac posttransplantation period was beneficial, with good hemodynamic tolerance and no related adverse effects.

Similarly, Finkel et al. described the beneficial effect of dexmedetomidine in discontinuing opioid treatment in 2 pediatric patients during the cardiac posttransplantation period.6 In the denervated heart, the pharmacodynamics of the medication depend on the site of action. Drugs that directly affect receptors in the donor heart will be effective, whereas those that act centrally or via autonomic reflexes will not produce the desired response.3 In our patients, dexmedetomidine was beneficial because of two mechanisms: first, it blocked the catecholaminergic response associated with withdrawal syndrome, reflected in the absence of hypertension and tachycardia; second, cardiac denervation prevented bradycardia, the principle adverse effect of dexmedetomidine. With regard to the latter, during the heart transplantation or pediatric heart surgery postoperative period most patients have pacemaker leads implanted, which enable us to increase their heart rate if necessary. These findings confirm the beneficial effects of dexmedetomidine not only to as an adjuvant to sedation but also to prevent postoperative withdrawal syndrome after heart surgery, and particularly heart transplantation. More thorough prospective studies are needed to establish protocols for its use.