Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP) is defined as a pain in the chest similar to that experienced in angina, but occurring in patients in whom heart disease has been ruled out.1 The literature shows that NCCP is associated with more psychiatric problems, 2 inadequate coping strategies,3 and neurosis4 than coronary heart disease (CHD). Although recent years have seen the undertaking of studies into NCCP and its related psychological factors5 and psychiatric comorbidity,6 much is still to be learned. The aim of the present work was to determine whether any psychological variables exist that might allow one to distinguish between NCCP and CHD.

This controlled, cross-sectional study involved patients attending the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Zaragoza for cardiology consultations between 2003 and 2005. Two groups of patients were established, those with NCCP consulting with regard to cardiac symptoms but who the attending cardiologist determined not to have heart disease (NCCP group), and patients with CHD attending the clinic owing to cardiac symptoms which the attending physician regarded as being of a cardiac nature (control [CHD] group). The tests used to confirm NCCP or CHD were blood analysis (for cardiac enzymes), an electrocardiogram, stress tests and coronary angiography, following the recommendations outlined in current clinical practice guidelines.7,8

The sample size for each group (n=40) was determined for a power of 80% with significance set at P=.05, two tails, and to detect a difference between groups in the psychological variables studied of 20%. A withdrawal rate of 10% was assumed. The initial sample size required was thus determined to be n=45, considering an expected refusal rate of 10%.

Sociodemographic information was collected from each subject, as well as a medical history including information on psychosocial variables: a) hostility (ICM-R9 Scale); b) personality (the Big Five Questionnaire,10 which records energy, affability, tenacity, emotional stability, and open-mindedness); c) coping (revised Coping Strategies Scale)11; d) alexithymia (Spanish adaptation of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale)12; e) psychosocial problems (Social Problems Scale)13; and f) quality of life (Quality of Life Scale).14

Quantitative variables were compared using the Student t test for paired samples when the distribution was normal, and the Friedman non-parametric test when not. Qualitative variables were analyzed via the calculation of the McNemar statistic (dichotomous variables). The remaining variables were analyzed using the c2 test, employing the Yates correction when necessary. The variables that differentiated the patient groups were identified by binary logistic regression calculating the area under the receiver-operator characteristics (ROC) curve. All calculations were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v.14.0.

This study was performed as part of wider research into functional somatic symptoms,15,16 and was approved by the Aragonese Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica de Aragón).

RESULTS

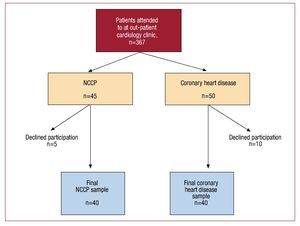

A total of 367 patients were examined to find 45 eligible patients with NCCP. Of these, 5 (11.1%) declined to take part in the study. The control patients with CHD, sex- and age-matched for the NCCP subjects, were also recruited from this initial group. A total of 50 patients with CHD were identified, but 10 (20%) declined to take part. No significant sociodemographic differences were seen between the subjects who declined to take part and those who did take part. Figure shows a flow diagram describing the study.

Figure 1. Flow diagram describing study. NCCP indicates non-cardiac chest pain.

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of both patient groups; no significant differences were seen between them. However, the CHD patients had more medical antecedents than the NCCP patients, while the latter had a lower quality of life. Table 2 describes the psychological variables recorded. No differences were seen between the patient groups with respect to hostility, social problems or searching for social support, but alexithymia was increased among the NCCP subjects. With respect to personality, the NCCP patients had lower emotional control scores, and in terms of coping, these patients relied more on religion and sought medical help more commonly than the CHD patients. Table 3 shows the logistic regression model, in which the following psychosocial variables proved to be predicitive: coping through religion, coping through seeking professional help, alexithymia and quality of life. This model allowed 82.7% of the subjects (sensitivity, 85.4%; specificity, 80%) to be correctly classified. The ROC curve value was 0.901.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to analyze the differences in psychosocial characteristics between patients with NCCP and those with CHD. The main limitation of this study is the sample size, which was small for a multivariate study; the results should therefore be considered preliminary. Further, these findings need to be confirmed in a prospective study in another population, in order to validate the discriminatory test.

No significant differences were seen between the 2 groups of patients in terms of sociodemographic variables. However, the quality of life of the NCCP patients was significantly poorer than that of the CHD patients. It has previously been reported that the quality of life of these patients is poorer than in any other somatic disorder.1

Although hostility appears to be a key factor associated with the development of CHD,17 it has also been shown to appear in patients with functional abnormalities,18 thus its presence does not allow one to distinguish between CHD and NCCP. No differences were seen between the patient groups in terms of their seeking social support or in terms of social problems. However, alexithymia was greater in the NCCP patients; this was expected since alexithymia is a risk factor for psychosomatic disorders.19

No difference was seen between the NCCP and CHD groups in terms of the Big Five score. Only the points scored on the emotional control subscale were different (lower in the NCCP subjects). With respect to coping, the NCCP subjects used two strategies more than the CHD patients: seeking medical help (in agreement with that reported by other authors),5 and reliance on religion, which leads to passivity in terms of dealing with their disease. It has been reported that in somatizing patients suffering chronic pain20 both these strategies are associated with uncontrollability and a perception of low self-efficacy, which in turn is related to a poorer quality of life and increased levels of physical and psychological incapacity.

The results of the multivariate analysis suggest a model for distinguishing between NCCP and CHD based on the variables alexithymia, coping via religion and coping via the seeking of medical help (sensitivity, 85.4%; specificity, 80%); this model correctly classified 82.7% of the patients. This is the first study to establish a method with high sensitivity and specificity that can distinguish between patients with these conditions. The specificity and sensitivity values described are similar to those of other psychological tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination, which is widely used in the early detection of dementia. The use of the present test could help physicians make a differential diagnosis between NCCP and CHD cheaply and quickly (the test only requires about 5 minutes to perform). Patients positive for NCCP could be quickly referred for mental health care, helping to avoid chronification problems and reducing costs, in many cases the confirmation of such a diagnosis by a psychiatrist would avoid the need for expensive complementary tests not free of iatrogenic risks. More studies should be performed to further develop this tool and to test its usefulness in everyday practice.

Red de Actividades Preventivas y de Promoción de la Salud (REDIAPP Preventive Activities and Health Promotion Network) (G06/128).

Correspondence: Dr. J. García Campayo.

Avda. Gómez Laguna, 52. 4 D. 50009 Zaragoza. Spain.

E-mail: jgarcamp@arrakis.es

Received November 16, 2008.

Accepted for publication June 22, 2009.