Acute heart failure represents the first cause of hospitalization in elderly persons and is the main determinant of the huge healthcare expenditure related to heart failure. Despite therapeutic advances, the prognosis of acute heart failure is poor, with in-hospital mortality ranging from 4% to 7%, 60- to 90-day mortality ranging from 7% to 11%, and 60- to 90-day rehospitalization from 25% to 30%. Several factors including cardiovascular and noncardiovascular conditions as well as patient-related and iatrogenic factors may precipitate the rapid development or deterioration of signs and symptoms of heart failure, thus leading to an acute heart failure episode that usually requires patient hospitalization. The primary prevention of acute heart failure mainly concerns the prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors and heart disease, including coronary artery disease, while the secondary prevention of a new episode of decompensation requires the optimization of heart failure therapy, patient education, and the development of an effective transition and follow-up plan.

Keywords

Acute heart failure (AHF) is the rapid development or change of signs and symptoms of heart failure that requires medical attention and usually leads to patient hospitalization.1–3 Acute heart failure represents the first cause of hospital admission in elderly persons in the western world and, despite advances in medical and device therapy, it still has unacceptably high morbidity and mortality rates. As a result, AHF represents a major public health issue, an enormous financial burden, and a challenge for current cardiovascular research.3

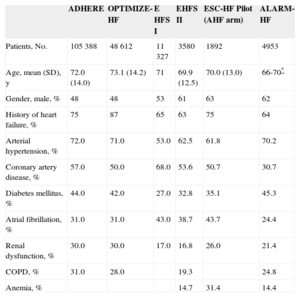

EpidemiologyA number of large-scale registries, such as the ADHERE4–6 and OPTIMIZE-HF performed in the United States,4–7 the EHFS I and II8–10 and the ESC-HF Pilot registry performed in Europe,8–11 as well as the international ALARM-HF12 have provided us with some epidemiological evidence on AHF.

Patients admitted for AHF are aged > 70 years and about half of them are male. Most have a previous history a heart failure, while de novo AHF represents only one-fourth to one-third of cases. About 40% to 55% have preserved LVEF (left ventricular ejection fraction). Those patients have a constellation of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular abnormalities. Concerning cardiovascular comorbid conditions, most AHF patients have a history of arterial hypertension, about half have coronary artery disease, and one-third or more have atrial fibrillation. In terms of noncardiovascular comorbidities, about 40% of patients admitted for AHF have a history of diabetes mellitus, about one-fourth to one-third have renal dysfunction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, while anemia is also present in 15% to 30% of patients. The main clinical features of AHF patients according to the aforementioned registries are outlined in Table 1.

Clinical Characteristic of Acute Heart Failure Patients in Different Registries

| ADHERE | OPTIMIZE-HF | E HFS I | EHFS II | ESC-HF Pilot (AHF arm) | ALARM-HF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | 105 388 | 48 612 | 11 327 | 3580 | 1892 | 4953 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 72.0 (14.0) | 73.1 (14.2) | 71 | 69.9 (12.5) | 70.0 (13.0) | 66-70* |

| Gender, male, % | 48 | 48 | 53 | 61 | 63 | 62 |

| History of heart failure, % | 75 | 87 | 65 | 63 | 75 | 64 |

| Arterial hypertension, % | 72.0 | 71.0 | 53.0 | 62.5 | 61.8 | 70.2 |

| Coronary artery disease, % | 57.0 | 50.0 | 68.0 | 53.6 | 50.7 | 30.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 44.0 | 42.0 | 27.0 | 32.8 | 35.1 | 45.3 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 31.0 | 31.0 | 43.0 | 38.7 | 43.7 | 24.4 |

| Renal dysfunction, % | 30.0 | 30.0 | 17.0 | 16.8 | 26.0 | 21.4 |

| COPD, % | 31.0 | 28.0 | 19.3 | 24.8 | ||

| Anemia, % | 14.7 | 31.4 | 14.4 |

ADHERE, Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry; AHF, acute heart failure; ALARM-HF, Acute Heart Failure Global Survey of Standard Treatment; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EHFS, EuroHeart Failure Survey; ESC-HF Pilot, European Society of Cardiology-Heart Failure Pilot registry; OPTIMIZE-HF, Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure; SD, standard deviation.

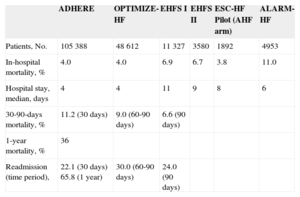

In most of the published AHF registries, in-hospital mortality ranges from 4% to 7% (Table 2), with the exception of ALARM-HF, in which mortality was as high as 11%, apparently due to the relatively higher proportion of patients with cardiogenic shock (around 12% vs < 4% in the rest of the aforementioned registries). The median length of hospital stay ranged from 4 days to 11 days. Postdischarge mortality up to 3 months was 7% to 11%, while 1-year postdischarge mortality reported by the ADHERE registry was 36%.5 Heart failure progression itself represents the cause of death in less than half of patients. According to data from the EVEREST trial,13 41% of AHF patients die of heart failure deterioration, 26% die suddenly, and 13% die of noncardiovascular comorbidities. It should be stressed that, although in-hospital mortality tends to be higher in patients with reduced LEVF compared with those with preserved LVEF, postdischarge morbidity is similar in the 2 groups.14

Acute Heart Failure Outcome in Different Registries

| ADHERE | OPTIMIZE-HF | EHFS I | EHFS II | ESC-HF Pilot (AHF arm) | ALARM-HF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | 105 388 | 48 612 | 11 327 | 3580 | 1892 | 4953 |

| In-hospital mortality, % | 4.0 | 4.0 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 11.0 |

| Hospital stay, median, days | 4 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| 30-90-days mortality, % | 11.2 (30 days) | 9.0 (60-90 days) | 6.6 (90 days) | |||

| 1-year mortality, % | 36 | |||||

| Readmission (time period), | 22.1 (30 days) 65.8 (1 year) | 30.0 (60-90 days) | 24.0 (90 days) |

ADHERE, Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry; AHF, acute heart failure; A LARM-HF, Acute Heart Failure Global Survey of Standard Treatment; EHFS, EuroHeart Failure Survey; ESC-HF Pilot, European Society of Cardiology-Heart Failure Pilot registry;OPTIMIZE-HF, Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure.

Postdischarge rehospitalization rates are quite high, as about one-fourth of patients are readmitted within 3 months, while two-thirds of them are rehospitalized within a year. It has been shown that the readmission rate follows a biphasic course consisting of 2 peaks, an early one during the first 2 to 3 months postdischarge and a late one during the final stage of the syndrome, separated by a long plateau phase with low admission rates.15

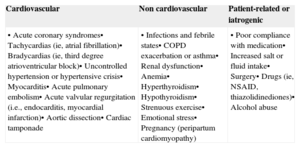

Risk factorsSeveral cardiovascular and noncardiovascular conditions may cause a rapid development or deterioration of signs and symptoms of heart failure leading to hospitalization. A detailed list of the causes and precipitating factors leading to AHF is provided in Table 3. Heart failure accounts for less than half of readmission causes. More specifically, according to the EVEREST trial, 46% of patients are admitted because of heart failure, while 39% are hospitalized because of noncardiovascular comorbid conditions.13

Causes and Precipitating Factors of Acute Heart Failure

| Cardiovascular | Non cardiovascular | Patient-related or iatrogenic |

|---|---|---|

| • Acute coronary syndromes• Tachycardias (ie, atrial fibrillation)• Bradycardias (ie, third degree atrioventricular block)• Uncontrolled hypertension or hypertensive crisis• Myocarditis• Acute pulmonary embolism• Acute valvular regurgitation (i.e., endocarditis, myocardial infarction)• Aortic dissection• Cardiac tamponade | • Infections and febrile states• COPD exacerbation or asthma• Renal dysfunction• Anemia• Hyperthyroidism• Hypothyroidism• Strenuous exercise• Emotional stress• Pregnancy (peripartum cardiomyopathy) | • Poor compliance with medication• Increased salt or fluid intake• Surgery• Drugs (ie, NSAID, thiazolidinediones)• Alcohol abuse |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSAID, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs.

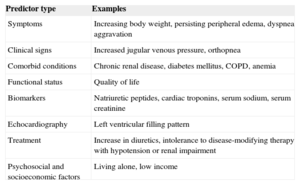

A number of clinical and laboratory parameters have been shown to predict AHF hospitalization (Table 4). Gradually aggravating symptoms and signs of congeston, deterioration of biomarkers such as natriuretic peptides or renal function parameters, increasing need for diuretics or intolerance to heart failure medication are the hallmarks of deterioration and thus of an upcoming AHF episode.15

Predictors of Postdischarge Rehospitalization for Acute Heart Failure

| Predictor type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | Increasing body weight, persisting peripheral edema, dyspnea aggravation |

| Clinical signs | Increased jugular venous pressure, orthopnea |

| Comorbid conditions | Chronic renal disease, diabetes mellitus, COPD, anemia |

| Functional status | Quality of life |

| Biomarkers | Natriuretic peptides, cardiac troponins, serum sodium, serum creatinine |

| Echocardiography | Left ventricular filling pattern |

| Treatment | Increase in diuretics, intolerance to disease-modifying therapy with hypotension or renal impairment |

| Psychosocial and socioeconomic factors | Living alone, low income |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Primary prevention of AHF concerns the prevention and early diagnosis and treatment of the causes of heart failure (Table 3) and mainly of cardiovascular risk factors and heart disease. Coronary artery disease is the cause in two-thirds of heart failure patients, particularly those with reduced LVEF, while arterial hypertension is found in approximately 70% of patients, particularly those with preserved LVEF.3 Therefore, timely and effective treatment of risk factors for atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, and arterial hypertension is expected to limit the occurrence of heart failure.

The secondary prevention of AHF concerns the prevention of chronic heart failure decompensation that leads to AHF episodes requirng hospitalization. As each hospitalization for AHF is known to confer additional deterioration of cardiac and kidney function, recurrent AHF episodes lead to a gradual decline of the patient's clinical course.16 As a result, the greater the number of hospital admissions, the worse patient survival.17 Furthermore, AHF hospitalization represents approximately 70% of the total expenditure on heart failure.18 Therefore, the secondary prevention of AHF episodes represents an important goal both in medical and socioeconomical terms.

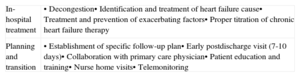

As previously stated, a significant proportion of readmissions occur during the first weeks postdisharge.15 It has been postulated that early readmissions are preventable in up to 75% of patients and that the main reasons for early readmissions are incomplete decongestion during the preceding hospital stay and a poor transition plan.19 Therefore, the strategies to prevent readmission mainly concern the optimization of in-hospital management of patients and the development of the patient transition and follow-up plan. These strategies are outlined in Table 5. It should be stressed that patient admission may also provide a chance for implementation or the titration of chronic heart failure therapy, better education, patient training, and the development of a follow-up plan.20

Strategies to Prevent Postdischarge Rehospitalization for Acute Heart Failure

| In-hospital treatment | • Decongestion• Identification and treatment of heart failure cause• Treatment and prevention of exacerbating factors• Proper titration of chronic heart failure therapy |

| Planning and transition | • Establishment of specific follow-up plan• Early postdischarge visit (7-10 days)• Collaboration with primary care physician• Patient education and training• Nurse home visits• Telemonitoring |

G. Filippatos is a member of steering committees of acute heart failure trials sponsored by Novartis, Cardiorentis, the European Union and Bayer. J. Parissis has received fees for conference presentations from Novartis International.