To the Editor,

.

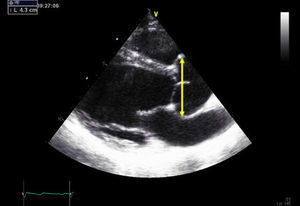

We present the case of a 29-year-old pregnant woman with Marfan syndrome who presented an aortic root diameter of <45 mm at the start of gestation with no other abnormalities. She had been diagnosed of Marfan syndrome 2 years previously as a result of a family study.1 The patient underwent a follow-up cardiologic examination before becoming pregnant. At that time, the aortic root diameter at the sinuses of Valsalva on transesophageal echocardiography was 43mm (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Transthoracic echocardiogram before pregnancy shows aortic root dilatation with a maximum diameter of 43 mm.

At week 30 of gestation, a dilatation of the abdominal aorta consistent with a thrombosed aneurysm was visualized on obstetric ultrasound. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the abdominal aortic aneurysm, which originated just below the superior mesenteric artery, continued to the aortic bifurcation, and had a maximum diameter of 58mm and an associated parietal thrombus; there was no evidence of thoracic aorta dissection or dilatation (Figure 2). On transthoracic echocardiography, the left ventricle showed no dilatation, systolic function was preserved (ejection fraction 55%), the right chambers were normal, and the ascending aorta was dilated at the sinus of Valsalva (45 mm).

Figure 2. Sagittal magnetic resonance image (unenhanced white blood sequence) shows the abdominal aortic aneurysm (arrow).

During pregnancy, the patient received beta-blocker treatment with maximum doses of atenolol (50mg/day), and blood pressure was well controlled (systolic arterial pressure <120 mmHg).

Following assessment by a multidisciplinary team (obstetricians, cardiologists, vascular surgeons, and anesthesiologists) to evaluate the maternal-fetal risk associated with this new finding, it was decided to finalize gestation at fetal maturity. Cesarean section was performed, and a baby boy was delivered (weight 1410g, Apgar 7 at 1min and 9 at 5min, arterial pH 7.4, and venous pH 7.5). The patient was discharged at 7 days following the cesarean, and surgical repair of the abdominal aortic aneurysm was scheduled. One month later, the patient was hospitalized, the abdominal aortic aneurysm was resected, and a 20-mm Dacron graft was placed from the distal thoracic aorta to the aortic bifurcation. During her intensive care unit stay, she required multiple transfusions, parenteral nutrition, and continuous renal replacement therapy due to acute kidney failure. At 17 days, the patient presented retrograde dissection of the thoracic aorta. Because of her critical situation, surgery was rejected as a treatment option in favor of emergency placement of a Cook endoprosthesis in the thoracic aorta. At 3 months posthospitalization, the patient was discharged in acceptable general condition.

A large number of cardiac complications have been reported in pregnant women with Marfan syndrome, the most characteristic being thoracic aorta dissection.2 Nonetheless, development of an abdominal aortic aneurysm during pregnancy in these patients has only been described previously as a finding during the puerperal period.3

Although most dissections occur in the ascending aorta, the descending thoracic aorta or abdominal aorta also can be affected. Aortic dissection can also occur in the low-risk group; that is, those without aortic dilatation.4 Although that is rare, these women should be informed that a normal echocardiogram does not indicate an absence of risk. The family history of aortic dissection and rapid growth of the aortic diameter should be included in risk assessment.1 It is essential to evaluate the entire aorta before and during pregnancy. Biomechanical assessment of aortic distensibility can help to identify patients without aortic dilatation who are at risk of dilatation or dissection.5

In pregnancies with a fetal gestational age of less than 28 weeks, the recommended treatment is aortic repair or medical treatment without finalizing pregnancy. When fetal gestational age is greater than 32 weeks, the recommended treatment is to finalize pregnancy by cesarian section with posterior aortic repair or medical treatment. In cases of gestational age between 28 and 32 weeks, the decision should be made on an individual basis by consensus between the mother and neonatalogists.6

This case illustrates the importance of performing abdominal ultrasound to monitor the size of the abdominal aorta, in particular after the second trimester of gestation when cardiac output increases. When any increase in the size of the aorta is documented on abdominal ultrasound, magnetic resonance is indicated to achieve a more precise assessment. The risk of aortic rupture or dissection secondary to development of a large dilatation or aneurysm is very high and implies a dismal prognosis.

All women with Marfan syndrome who wish to have a baby should be evaluated and counseled by a multidisciplinary team, primarily a cardiologist and obstetrician, with individualized determination of the associated risk.6

Corresponding author: mariagoya@mac.com